Market Access & Health Technology Assesment: Switzerland

Market Access & Health Technology Assesment: Switzerland answers essential questions about this environment for pharmaceuticals in Switzerland. It is a must-have asset for any company operating in Switzerland or looking to enter the market.

Market Access & Health Technology Assesment: Switzerland answers essential questions about this environment for pharmaceuticals in Switzerland. It is a must-have asset for any company operating in Switzerland or looking to enter the market.

Prepared in association with Wenger Plattner, one of the leading corporate law firms in Switzerland.

February 2023

1. Healthcare System and Funding: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Please make a general introduction to the public health sector in your country and its organization

The Swiss healthcare system is shaped by the federal structure of Switzerland. That is, federal government (in particular the Federal Office of Public Health, see chapter II question 1 A below), the cantonal governments and the local municipalities assume different tasks in the healthcare system. This results in a complex, fragmented healthcare system. Moreover, the Swiss healthcare system is shaped by a complex interplay of the state and the private sector.

Globally, the quality of the Swiss healthcare system is considered superior. As a principle, healthcare of high quality is available nationwide for everyone. There exists a dense network of physicians and hospitals. In most medical areas, patients do not have to wait long for a treatment. On the other hand, the Swiss healthcare system causes very high costs (roughly 83 billion Swiss Francs in 2020, which is 9,600 Francs per person / year or 11% of the Swiss GDP), a problem which has been increasingly addressed by Swiss politics over recent decades. The hospital sector is the largest cost block among the service providers in the healthcare system and is responsible for more than one third of the total healthcare costs in Switzerland.

One of the central pillars of the Swiss healthcare system is the basic health insurance which is compulsory for every Swiss resident (see chapter II question 1 E below). The coverage of the compulsory insurance is set by the FOPH. It encompasses access to most basic treatments and medicines in case of illness, accident and motherhood, as well as access to certain examinations for the early detection of diseases and precautionary measures for people at increased risk (e.g., vaccines). The compulsory insurance is financed by state-fixed premiums of the policy holders.

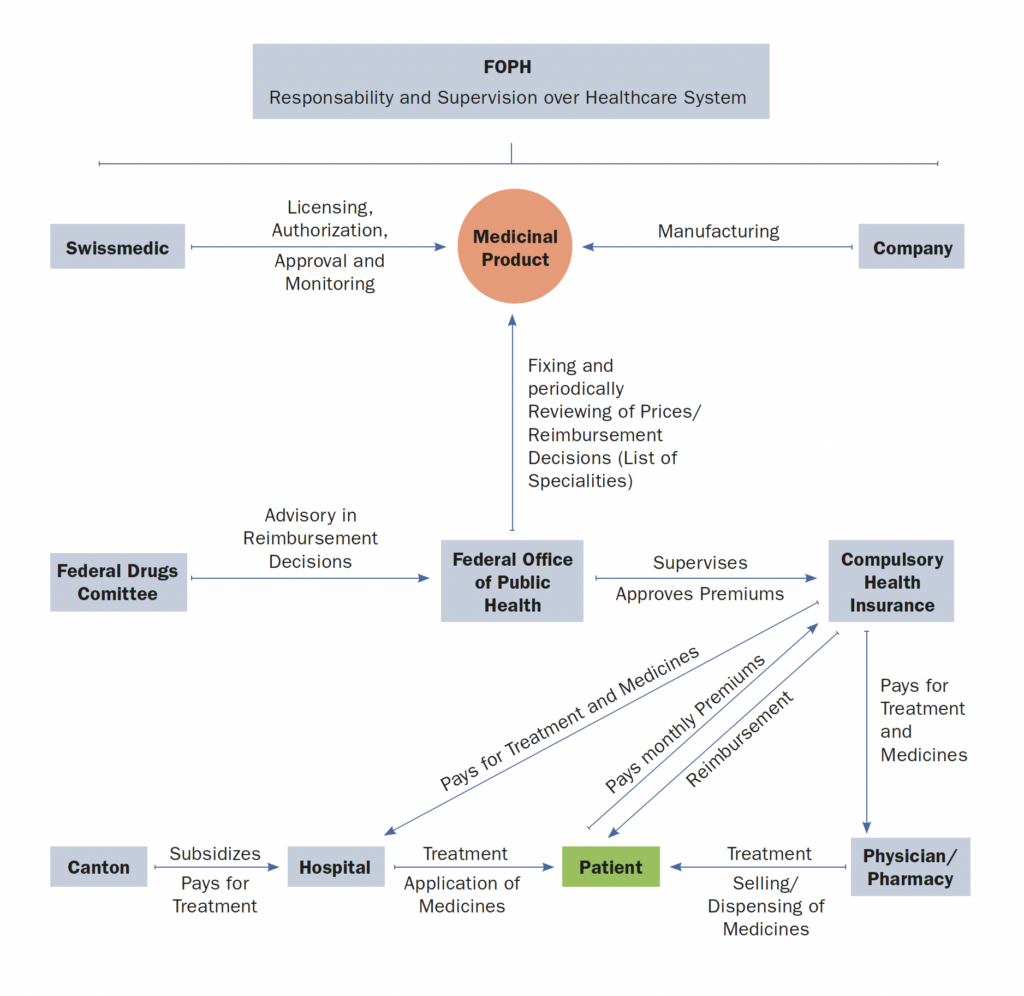

2. Please provide any infographics including

a. The actors involved in the market access process (market authorization, pricing decisions, reimbursement decisions)

b. The information and data required

c. The process and flow

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

2. Healthcare Actors and Payers: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of public health in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

a. Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH; Bundesamt für Gesundheit)

The FOPH is attached to the Federal Department of Home Affairs (FDHA; Eidgenössisches Departement des Innern). The FOPH is responsible for the national health policy of Switzerland. The FOPH coordinates Swiss healthcare policy and advocates for a long-term efficient and affordable healthcare system. Further, the FOPH supervises the Swiss health system, especially the compulsory healthcare insurance. As the federal authority, the FOPH represents Switzerland in health policy matters in international organizations and vis-à-vis other countries.

The FOPH is – together with the cantons – responsible for the health of the Swiss population. E.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic, the FOPH enacted measures to protect the population from the disease.

It is within the responsibilities of the FOPH to make reimbursement decisions, to set and review the prices of reimbursable, therapeutical products and to set the premiums of the Compulsory Health Insurance.

b. Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products (Swissmedic; Schweizerisches Heilmittelinstitut Swissmedic)

Swissmedic is a federal institute which is attached to the FDHA. It is the competent authority for most authorizations and licenses in the field of therapeutic products. The legal basis of Swissmedic is the Federal Therapeutic Products Act (TPA; Heilmittelgesetz, HMG, SR 812.21).

Swissmedic is financed by fees, by payments from the federal government in return of services of public interest and from services rendered to third parties. The public services are described in a service mandate from the Swiss federal administration (Federal Council; Bundesrat) and in an annual service agreement with the FDHA. To ensure the efficiency of its control activity, the Agency is managed according to the principles of good business practice.

c. The cantons

Historically, healthcare was an exclusive cantonal competence in Switzerland. Also, in today’s healthcare system of Switzerland, the Cantons are one of the central (if not the most important) actors. According to Art. 117a of the Swiss Constitution, the confederation and the cantons shall ensure, each one within the scope of its competences, that sufficient basic medical care of high quality is accessible to everyone. E.g., the cantons are responsible for disease prevention and for the hospital planning. Accordingly, each canton enacts its own health laws.

However, the sphere of competence of the Swiss Federation and the federal government has increased over time in many areas, and so it has in the healthcare sector. According to Art. 117 and 118 of the Swiss constitution, the Swiss Federation is competent to enact rules on health insurance and on the handling of medicines and on the control of communicable, widespread or malignant diseases. As a consequence, at the latest since the enactment of the Federal Health Insurance Act (HIA; Bundesgesetz über die Krankenversicherung, KVG, SR 832.10) in 1994, many important healthcare issues are regulated on a national level. The division of responsibilities between the federal government and the cantons is not always sharp. As a consequence, the responsibilities sometimes overlap. This becomes noticeable especially in times of crisis, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Responsibility for healthcare at the cantonal level lies with the health directorate of the respective canton. According to Swiss doctrine of federalism, the cantons are vested with the competence to implement and enforce the national law. Therefore, in addition to the cantonal laws for health issues which are in the competence of the cantons, each health directorate issues autonomous cantonal laws to implement and enforce the national health laws. This effectively results in 26 cantonal health systems.

d. Conference of Ministers of Public Health (HMC; Gesundheitsdirektorenkonferenz, GDK)

The HMC, consisting of the Ministers of all cantonal health directorates, coordinates the policies of the different cantonal health system. The HMC has an important function as a hub between the cantons among each other, between the cantons and the Confederation, as well as between the cantons and the other actors in the healthcare system.

e. Compulsory Health Insurances

Every Swiss citizen must join a compulsory health insurance (Art. 3 para. 1 HIA). Everyone can freely choose the compulsory health insurance, irrespective of their age, health or other conditions (Art. 4 HIA).

According to Art. 4 of the Federal Health Insurance Supervision Act (HISA; Krankenversicherungsaufsichtsgesetz, KVAG, SR 821.12), the compulsory health insurance is provided by private or public health insurance companies which are authorized by the FOPH to operate in accordance with the provisions of the HIA. Within the scope of the compulsory insurance, the insurance companies operate on a non-profit oriented basis (Art. 2 para. 1 HISA).

The benefits which are included in the compulsory insurance are set by the FOPH (see chapter III question 3 below). It encompasses access to most basic treatments and medicines in case of illness, accident and motherhood, as well as access to certain examinations for the early detection of diseases and precautionary measures for people at increased risk (e.g., vaccines).

The insurance companies are supervised by the FOPH in accordance with the HISA (Art. 56 HISA). For example, the compulsory health insurance companies must have their business activities audited every year by an external auditing body that is independent of them and recognized by the Government (Art. 25 HISA). Further, the premiums are supervised and approved by the FOPH (Art. 16 HISA).

f. Supplementary Health Insurance

In addition to the compulsory insurance, there exist supplementary insurance plans which cover treatments and medicines that are not included in the basket of benefits of the compulsory insurance, such as dental treatment or single-room accommodation during hospitalization. Such supplementary insurances may also be offered by the insurance companies which provide the compulsory insurance. In this case, the supplementary insurance is not governed by the HIA but by the Federal Insurance Contract Act (Art. 2 para. 2 HISA).

In contrast to the compulsory insurance, within the scope of the supplementary insurance, there is freedom of contract, i.e., insurance companies are not obliged to insure applicants. Moreover, the supplementary insurance is profit oriented.

2. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of drug approvals in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

The main authority for drug approvals in Switzerland is Swissmedic (Art. 9 TPA). In fact, Swissmedic is involved in the entire life cycle of a medicinal product due to its mandated areas of responsibility in the sectors of licensing, authorization and monitoring of medicinal products.

Originator medicines are approved according to the requirements of Art. 10 TPA. The proceeding is regulated in Art. 11 TPA.

The marketing authorization procedure for generic medicinal products is governed by Art. 12 TPA. According to this provision, the application for a marketing authorization for a medicinal product which is essentially the same as a medicinal product whose documents are protected, may be based on the results of the pharmacological, toxicological and clinical tests if (a) the holder of the marketing authorization provides its written permission or (b) the protection period for the relevant documents has expired.

3. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions that qualify as “payers” in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

The Swiss healthcare system is financed by three major payers: The compulsory health insurance, the individual self-payers and the state (mostly the cantons).

a. Compulsory Health Insurance

The central payer in the Swiss healthcare system is the compulsory health insurance. The compulsory insurance is in return financed by the policyholders, i.e., by the Swiss population, through monthly premiums. Employers do not participate in the premiums of the compulsory insurance, but they do contribute to the accident insurance for accidents at work.

The premiums are yearly set by the insurance companies (Art. 61 para. 1 HIA). In general, all policy holders must be treated equally, i.e., the premiums are independent of income, gender or health condition of the policyholder. However, the amount of the premium may (and in practice does) vary between the different regions (canton of residence) (Art. 61 para. 2bis HIA). Insurance companies must set lower premiums for young adults (19 to 25 years) and for children (until 18 years) (Art. 61 para. 3 HIA). Further, the premium depends on the deductible (“Franchise”) which the policyholder can chose. The FOPH supervises and approves the premiums set by the insurance companies (Art. 16 HISA).

b. Self-payers and supplementary health insurance

Despite the existence of a compulsory health insurance, Swiss residents pay for many healthcare services by themselves.

First, many healthcare services are – contrary to some other European countries – not contained in the benefit basket of the compulsory health insurance, such as glasses and contact lenses (only for children under 18 years), ambulance rides (only 50% and max. CHF 500 per year), dentist and dental care (only in cases of severe diseases, e.g., of the masticatory system), gynecological checkups (only every 3 years), contraceptives, typical travel vaccinations (e.g., malaria prophylaxis) and yearly flu vaccinations (only for persons in the risk group).

Moreover, in 2018 out of ca. 9,000 authorized drugs in Switzerland, only about 3,000 were on the list of specialities (see below chapter III question 3), i.e., around two third of the authorized drugs are not reimbursable.

Hence, many healthcare services, treatments and drugs are widely applied for and consumed by Swiss patients on a self-payer basis. Some of the costs are covered by supplementary health insurances.

Finally, in addition to the premiums of the compulsory health insurance, Swiss patients must bear the yearly deductible (Art. 64 para. 2 lit. a HIA). According to Art. 93 para. 1 of the Ordinance on Health Insurance (HIO; Verordnung über die Krankenversicherung, KVV, SR 832.102), most insurance companies offer models where the patient can choose the deductible (adults: CHF 300 – 2’500 per year; children CHF 100 – 600 per year). Moreover, patients participate with an excess of 10% (Art. 64 para. 2 lit. b HIA) and for some drugs with an excess of even 20% (Art. 38a para. 1 of the Ordinance on Healthcare Service (OHCS; Krankenpflege-Leistungsverordnung, KLV, SR 832.112.31)). According to Art. 64 para. 3 HIA and Art. 103 para. 2 HIO, the excess is limited (adults: max. CHF 700 per year; children: max. CHF 350).

c. The cantons

Many of the public health costs are borne by the cantons. As the premiums and self-payments do not suffice to finance the Swiss health system, the state finances different healthcare services. For example, cantons must contribute at least 55% of the costs for inpatient hospital treatment of patients who live in the respective canton (Art. 49a para. 2 and 2ter HIA). The compulsory health insurance pays for the remaining share (maximum 45%). In addition, the uncovered costs of hospitals from the cantonal hospital list are often subsidized by the canton.

Further, according to Art. 65 HIA, the cantons grant premium reductions to insured persons in modest economic circumstances.

4. Which are the administrations, bodies, and institutions in charge of pricing decisions in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

The authority in charge of pricing decisions is the Health Insurance Benefits Division (HIBD) which is attached to the FOPH. The FOPH fixes the prices of medicines (Art. 52 para. 1 lit. b HIA) and reviews the set price triennially in accordance with Art. 65d para. 1 HIO. If the FOPH finds that the price is too high, it can reduce the price (Art. 65d para. 4 HIO).

See in detail under chapter IV below.

5. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of reimbursement decisions in your countries and what are their respective responsibilities?

The administrations in charge of reimbursement decisions are the FDHA and the FOPH (Art. 52 para. 1 lit. b and Art. 33 para. 5 HIA). The FOPH decides on the admission of a drug to the list of specialities (see chapter III question 3 below). In its decision, the FOPH is being advised by the Federal Drugs Commission (FDC; Eidgenössische Arzneimittelkommission, EAK) (Art. 34 and 37e HIO). The FDC is an extra-parliamentary committee, consisting of 16 members and composed on a parity basis (Art. 37e HIO).

See in detail under chapter III questions 3 and 4 below.

6. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in your countries and what are their respective responsibilities?

The costs of the Swiss healthcare system have more than doubled in 20 years (from 37.5 billion Swiss Francs in 1996 to 77.8 billion Swiss Francs in 2015). In order to damper the costs, the Federal Council, based on Art. 32 HIA, launched a program in 2015 that evaluates – with methods of Health Technology Assessment – services which are currently reimbursed by the compulsory health insurance. The aim is to remove medical services from the benefits catalogs that no longer meet the criteria of efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness (see in detail chapter III question 3 below). The program is overseen by the Health Technology Assessment Section, a committee attached to the HIBD (see in detail chapter V question 1 below).

7. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of public procurement and tendering in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

Since its entry into force on 1 January 1996, the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement (WTO GPA) has formed the foundation of public procurement law in Switzerland. It contains substantial minimum requirements for the award of contracts in the area of trade in goods and services as well as construction contracts.

With certain exceptions, public procurement law remains largely within the competence of the cantons. In order to facilitate the implementation of the WTO GPA at the cantonal level, the 26 cantons agreed on an inter-cantonal agreement on public procurement (ICAPC; Interkantonale Vereinbarung vom 15. November 2019, IVöB).

On the other hand, procurements of the federal administration are subject to the Federal Public Procurement Act (PPA; Bundesgesetz über das öffentliche Beschaffungswesen, BöB, SR 172.056.1).

In general, all cantonal and municipal administrations, as well as cantonal legal entities organized under public law, are subject to the procurement law in both the scope of the GPA treaty and the scope of Swiss national procurement laws. The same applies for other authorities, public organizations and private companies in specific sectors, such as water, energy and traffic. Other organizations (public and private) as well as objects and services that are more than 50% subsidized by public funds are also subject to the rules of procurement laws, however only in the scope of Swiss national procurement laws, and not in the scope of the WTO GPA.

Private service providers in accordance with Art. 35 para. 2 HIA, which are on the hospital list and undertake procurements in the field affected by the hospital list and/or within the scope of a public contract, are subject to the provisions of public procurement. However, if the private service provider in accordance with Art. 35 para. 2 HIA is not on the hospital list, the rules of public procurement will only be applicable if the service provider performs a public service or receives state funds and only for such procurements in the field of the public service provided.

8. What are the other actors of significance with regards to market access in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

Another important actor is the drug stores, which sell both over the counter (OTC) and prescription drugs. Pharmacies are regulated on a cantonal basis. 78 percent of the Pharmacies belong to the association of pharmacies “pharmaSuisse”.

Medical practitioners are important actors as well. Physicians are organized in cantonal associations which are united in the umbrella organization “FMH”. Many Swiss cantons allow physicians to dispense all or certain medicinal products themselves (see below chapter X question 1 g).

Finally, hospitals are actors of great significance. There are private, state-owned and state-subsidized hospitals. Each canton must coordinate the planning of hospitals for its territory and to keep a so-called hospital list (Art. 39 HIA). For hospitals that are on the cantonal hospital list, the canton and the compulsory healthcare insurance have a full payment obligation (Art. 41 para. 1bis HIA).

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

3. Post Market-Approval Processes and Regulations: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. What are the pricing models, processes and principles for originator drugs?

An original drug is defined as a drug approved by Swissmedic as the first drug with a specific active ingredient, including all dosage forms approved at the same time or later (Art. 64a para. 1 HIO).

In Switzerland, only the price of pharmaceuticals which are included in the list of specialities (see question 3 below), is regulated by the government. On the other hand, prices of non-reimbursed OTC are freely set by the manufacturers.

The drug price is determined such that the product meets the rule of cost-effectiveness (for the criteria of cost-effectiveness, see in detail under question 3 below). A drug is considered cost-effective if it ensures the indicated healing effect at the lowest possible financial cost (Art. 65b para. 1 HIO). The cost-effectiveness is then assessed by external and internal reference pricing (Art. 65b para.2 HIO, see in detail under chapter IV below).

The price so determined is not final. The FOPH further considers costs for research and development (unless the original product is a successor product that does not bring any therapeutic progress). In case of significant therapeutic progress, a so-called innovation supplement is granted for a maximum of 15 years (Art. 65b para. 6 and 7 HIO).

2. What are the pricing models, processes and principles for generics and biosimilars drugs?

A generic drug is defined as a drug approved by Swissmedic which is essentially the same as an original drug and which is interchangeable with the original drug due to identical active ingredients as well as its dosage form and dosage (Art. 64a para. 2 HIO).

Just like originator products, in order to be reimbursable, generics too, must meet the rule of cost-effectiveness, i.e., the price of generic products is regulated such that the product is cost-effective. However, the cost-effectiveness of a generic product is assessed according to the so-called price gap rule. This rule takes into account that the development costs incurred for generics are generally lower than for the originator product (Art. 65c HIO).

Depending on the annual turnover (less than 4, 4 to 8, 8 to 16, 16 to 25 or more than 25 Mio. Swiss Francs) in the three years before expiration of the patent of the originator product, the generic drug must be (at least 20, 30, 50, 60 or 70%, respectively) cheaper than the originator counterpart (Art. 65c para. 2 HIO).

The starting point for price determination is the ex-factory price of the originator product at patent expiry (Art. 65c para. 2 HIO). After the patent for an originator product expires, an external and an internal price comparison are made, with both being weighted equally.

As a result, the prices of Swiss generics are also (albeit indirectly) determined by a comparison with European drug prices. Still, the prices of generic products in Switzerland are more than twice as high than the prices of the respective generic product in the other European reference countries (see below chapter X, question 1 a).

A biosimilar is considered cost-effective if at the time of the application for inclusion in the list of specialities (see question 3 below), its ex-factory price is at least 25% lower than the price of the corresponding originator product (whose patent has expired), which has been reviewed at the foreign average price level in accordance with Art. 65e HIO. At the triennially review, the price must be at least 10% lower than the respective originator drug, otherwise, the FOPH will lower the price.

3. What are the reimbursement approval processes and principles for originator drugs?

Art. 25 – 31 HIA and the OHC define in detail which healthcare services are reimbursable by the compulsory health insurance.

With regards to drugs, the FOPH publishes the so-called “list of specialities” (LS) which is basically the list of reimbursable drugs (Art. 52 para. 1 lit. b HIA). The LS is available at http://www.spezialitaetenliste.ch (last visited on 19 January 2023).

To be included in the LS, an application must be filed with the FOPH (Art. 31 para. 1 lit. a HIO). According to the law, the approval should not take longer than 60 days from the date of the market authorization (Art. 31b OHCS).

Requirements

According to a leading principle of the Swiss healthcare system, laid down in Art. 32 para. 1 HIA and Art. 65 para. 3 HIO, healthcare services and drugs are only reimbursable if they meet three criteria: they must be effective, suitable and cost-effective. These so called WZW[1]-criteria of efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness are periodically reviewed (Art. 32 para. 2 HIA).

For drugs, the three criteria are defined as follows:

Efficacy: The assessment of the efficacy of (allopathic) drugs must be based on clinically controlled studies (Art. 65a HIO). For the assessment of the efficacy, the FOPH relies on the same documents that were used in the drug approval procedure by Swissmedic. However, the FOPH may require that further documents be submitted (Art. 32 OHCS).

Suitability: The suitability of a drug regarding its effect and composition is assessed according to clinical-pharmacological and galenic considerations, undesirable effects and the risk of misuse (Art. 33 OHCS).

Cost-effectiveness: A drug is considered cost-effective if it ensures the indicated healing effect at the lowest possible financial cost (Art. 65b para. 1 HIO). The cost-effectiveness is assessed by external and internal reference pricing (Art. 65b para. 2 HIO).

In practice[2], these criteria are operationalized (i.e., concretized) as follows:

A medical service is effective if (1) it is suitable for achieving the intended diagnostic or therapeutic goals, (2) the benefit has been proven in clinical studies, (3) there is favorable ratio of benefit to harm compared to alternative diagnostic or therapeutic procedures, and (4) the transferability of the study results to the Swiss application setting can be assumed.

A medical service is suitable if (1) it is relevant and suitable for patient care compared to alternatives, (2) it is compatible with legal frameworks, social and ethical aspects or values, and (3) quality and appropriate application in practice is ensured.

A medical service is cost-effective if (1) its rates and prices are comprehensibly fixed and (2a) it has a favorable cost-benefit ratio in terms of direct healthcare costs compared to alternative procedures, or (2b) the additional costs are offset by a corresponding additional benefit and the cost impact on the mandatory healthcare insurance is acceptable.

4. What are the reimbursement approval processes and principles for generics and biosimilar drugs?

The LS contains both originator and generic pharmaceutical products (Art. 52 para. 1 lit. b HIO). In general, just like originator products, generics must meet the three WZW-criteria of efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness, in order to be included in the LS.

However, the following specific rules apply for generics and biosimilars:

Generics

For a generic product to be included in the SL, it must be interchangeable with the originator product. Concretely, the manufacturer must submit the authorization decision of Swissmedic stating that the bioequivalence with the original product has been demonstrably checked in the authorization procedure.

Moreover, generics are considered suitable, if all package sizes and dose strengths of a dosage form (galenic form) of the original preparation for adults are registered. Further, all indications of the originator product must also be covered by the generic product. If this is not complied with, this must be justified on medical-therapeutic grounds or, if applicable, with an existing patent or first filing protection. A purely economic justification is not sufficient.

Regarding the criterion of cost-effectiveness, see above question 2.

Biosimilars

The manufacturer of a biosimilar must submit Swissmedic’s authorization decision stating that it is a biosimilar of a reference (original) product.

Unlike manufacturers of generic products, manufacturers of biosimilars must submit additional documentation regarding quality, patient safety and, in some cases, even similar comparative studies as for originator products.

Regarding the criterion of cost-effectiveness, see above question 2.

*The FOPH has published a “basic document: Operationalization of the criteria ‘efficacy, appropriateness and cost-effectiveness’ according to Article 32 of the Federal Health Insurance Act” (https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/kuv-leistungen/bezeichnung-der-leistungen/operationalisierung_wzwkriterien_310322.pdf.download.pdf/Operationalisierung%20der%20WZW-Kriterien%20vom%2031.03.2022,%20g%C3%BCltig%20ab%2001.09.2022.pdf).

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

4. Price Control and Reference Pricing Systems: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Price Control

1.1. How does price control at ex-factory prices work in your country?

Price control is regulated in Art. 65d HIO. Triennially, the FOPH reviews whether the medicinal products included in the LS still meet the WZW-requirements (see above chapter III question 3). The medicinal products are divided into three categories, whereby each category is reviewed triennially (Art. 65d para. 1 HIO).

Ex-factory prices, wholesale prices and retail prices of medicinal products are reviewed jointly as part of the triennial price review. The basis for the review is the maximum price of a medicinal product as stated in the LS. The maximum price is defined as the ex-factory price plus the wholesale share (Art. 67 para. 1bis HIO). The ex-factory price covers the services of the manufacturing and distribution company up to the point of shipping from the factory (Art. 67 para. 1ter OHI). The wholesale share is composed of a surcharge covering the logistical services (Art. 67 para. 1quater HIO). After the addition of VAT, the maximum price listed in the LS corresponds to the retail price of the respective medicinal product as charged by pharmacies, doctors, and hospitals.

The price review is conducted by comparing the maximum price of the medicinal product with reference prices of the same medicinal product in other countries (external reference pricing), as well as by a therapeutic cross-comparison (internal referencing pricing) between the medicinal product reviewed and other medicinal products (Art. 65b para. 2 HIO). The average price in the reference countries (external reference price) and the average price for similar medicinal products (internal reference price) are each weighted equally (Art. 65b para. 5 HIO).

The comparison with the reference prices in other countries is done based on the bestselling unit of the respective medicinal product. The therapeutic cross-comparison is conducted based on the smallest unit and dosage of the respective medicinal product (Art. 65d para. 2 and 3 HIO). If the review concludes that the current maximum price is too high, the FOPH orders a price reduction to the appropriate price (Art. 65d para. 4 HIO).

1.2. How does price control at the wholesale level work in your country?

Considering that the wholesale prices or surcharges are already factored into the triennial price review, the abovementioned price control system under question 1 above also applies for this question.

1.3. How does price control at the retail pharmacy level work in your country?

The retail price of medicinal products corresponds to the maximum price as per the LS (ex-factory price plus wholesale surcharge plus VAT) and is reviewed triennially as described under question 1 above.

2. External Reference Princing (ERP)

2.1. Is there a system of external reference pricing (ERP) in place in your country?

Yes, before a medicinal product is approved and placed on the LS, the legal requirements regarding efficacy, suitability, and cost-effectiveness (WZW-criteria) must be met (Art. 65 para. 1 and 3 HIO). Triennially, the price is reviewed whereby it is assessed whether the WZW-criteria are still fulfilled. Thereby, external reference pricing builds a part of the assessment of the criterion of cost-effectiveness.

2.2. When and/or how often is ERP activated?

ERP is initially activated before a medicinal product is admitted to the LS to determine whether the product is cost-effective. Additionally, an ERP test is conducted triennially as part of the re-evaluation whether the criterion of cost-effectiveness is still met.

2.3. What is the legal framework of the ERP in place in your country?

Art. 32 HIA sets out three conditions for the reimbursement of medicinal products: efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness (see above chapter III question 3). Art. 65d para. 2 lit. a HIO stipulates that the requirement of cost-effectiveness is assessed, inter alia, by an external reference pricing process. The details of the implementation of such an ERP are further regulated in Art. 34abis – Art. 34e HCSO.

2.4. What is the composition of the country basket?

The country basket consists of Germany, Denmark, Great Britain, Netherlands, France, Austria, Belgium, Finland and Sweden. In addition, a comparison with other countries with comparable economical structures may be conducted if the ex-factory price, the wholesale price, or the retail pharmacy price are publicly known (Art. 34abis para. 1 HCSO).

2.5 Describe the price calculation and selection for reference products.

ERP is conducted by comparing the Swiss medicinal product with the same medicinal products in the reference countries, regardless of its name. A product is deemed to be the same if the active ingredients and the dosage forms are identical (Art. 34a HCSO). The ex-factory price of the Swiss medicinal product is compared to the ex-factory price of the reference countries whereby the bestselling unit of the respective medicinal product is selected for the ERP (Art. 65d para. 2 HIO). If the ex-factory price is not public in the respective country, the retail pharmacy price is taken into consideration. If the latter is not public either, the wholesale price is taken as a basis for the calculation. Average retail or wholesale margins for the respective countries as well as mandatory discounts are then deducted from the price (Art. 65b para. 3 and 4 HIO and Art. 34b HCSO).

2.6. How often does the price need to be updated?

There is no general obligation to update the prices. However, if the triennial review concludes that the prices are too high compared to the reference countries, the FOPH orders a price reduction. The authorization holders also have the option to apply for a permit to increase the price of the respective medicinal product. Such requests may be granted by the FOPH if the product still satisfies the conditions for admission to the LS and if at least two years have passed since the last price increase (Art. 67 para. 2 HIO).

2.7. How do the “price List”/catalogues from references countries work in your country?

The FOPH retrieves the prices from publicly available sources. All reference countries have publicly available information on their drug prices.

3. Internal Reference Pricing (IRP)

3.1. Is there an internal reference pricing (IRP) system in your country?

Yes. Besides the ERP system explained in the previous section, the cost-effectiveness of a medicinal product, as one of the criteria for its admission on the LS (and for the triennial review), is assessed with an internal reference pricing system.

By way of IRP, the medicinal product to be admitted or price-reviewed is compared with other medicines authorized in Switzerland that are used to treat the same condition. The FOPH compares specifically the efficacy as well as the cost of the reviewed medicinal products per day or per treatment in relation to such other medicinal products.

3.2. What is the legal framework of the IRP in place in your country?

Art. 32 HIA sets out three conditions for the reimbursement of medicinal products: efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness (see above chapter III question 3). Art. 65d para. 2 lit. b HIO provides for an IRP to be conducted as part of the assessment of the criterion of cost-effectiveness. Specific rules for the IRP are found in Art. 65b para. 4bis and Art. 65d para. 3 HIO as well as in Art. 34f HCSO.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

5. HTA Decision Analysis Framework: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Which are the health technology assessment (HTA) evaluation bodies and their responsibilities in your country?

The National HTA program is overseen by the Health Technology Assessment Section (HTAS) of the HIBD (see above chapter II question 1). Further involved with the preparation and the decision-making process of the HTA dossiers are the Federal Medical Services Commission (FMSC; Eidgenössische Kommission für allgemeine Leistungen und Grundsatzfragen, ELGK) and the FDC.

HTA topics can be submitted to the HTAS by the public at any time (see link in chapter VI question 3). From all submissions, the HTAS choses, upon recommendation of the FMSC and the FDC, the topics for HTA review and opens a dossier for each topic that will undergo a HTA analysis.

In a pre-scoping procedure, the HTAS conducts a preliminary analysis and defines the questions to be investigated. After the pre-scoping, an external partner is commissioned in a tender process.

The external partner creates a protocol where the research questions and the methodology are defined in detail. Thereafter, the protocol is submitted to stakeholders, consisting of health insurance associations, patient organizations, industry associations or other interested parties for their comment. The protocol is published on the HTA projects page, available on https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/hta/hta-projekte.html (last visited on 19 January 2022).

In a next step, the external partner analyses the scientific evidence of the product in question and creates a report on its findings. The report must address the questions of efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness of the reviewed product. The report is submitted to a review group which evaluates the scientific quality of the report. The report is as well submitted to the stakeholders for their comments.

Finally, the report is appraised by the FMSC and the FDC. Theses to commissions submit a recommendation to either the FOPH, if the HTA concerns medicinal products, or otherwise to the FDHA. The FOPH or FDHA decide whether mandatory reimbursement of the product in question is continued, restricted or terminated.

2. Do regulators require HTA studies in your country?

HTA studies are not required by the FOPH but they are viewed as an important tool to base health policy-making on.

3. Do payers require HTA studies in your country?

The compulsory insurance companies do not require HTA studies to be conducted.

4. How are HTA assessments translated into pricing conditions in your country?

HTA assessments are not directly translated into pricing conditions, but they build the basis for the decision of the FOPH or FDHA regarding price adjustments of a medicinal product on the LS.

5. How are HTA assessments translated into reimbursement conditions in your country?

HTA assessments are not directly translated into reimbursement conditions, but they build the basis for the decision of the FOPH or FDHA regarding continuation, termination, or restriction of a medicinal product on the LS.

6. Which are the evaluation criteria, processes or models and analyses framework used for HTA in your country?

There is no framework published by official sources regarding the evaluation of HTA. There is, however, a published consensus paper on HTA in Switzerland (http://www.swisshta.org/index.php/Consensus.html), prepared by a group of several stakeholders, including the Swiss Medical Association, Interpharma (an association of Switzerland’s research-based pharmaceutical industry), the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences and santésuisse (an association of around 40 Swiss health insurance companies) and the FOPH, whereby the latter had only an observer status. This consensus was presumably taken as a basis for the Swiss HTA program of the Federal Council which started in 2015.

Key points of this consensus include, inter alia, the clear separation of assessment, appraisal and decision-making as well as transparency of the process, the criteria and the decisions. Emphasis is further laid on a practice-oriented application of the principles of evidence-based medicine and on a consistent systematization of the three WZW-criteria of efficacy, suitability, and cost-effectiveness.

7. What is the methodology used in your country for HTA assessment?

No pre-determined methodology exists. For each HTA dossier, the methodology is defined individually by the external partner in the HTA protocol.

8. Which are the other decisions impacted by the assessed outcome in your country?

It is likely that providers or authorization holders of medicinal products and services will take note of the HTA results and can take them into account in their decisions regarding the production and distribution of their products on the Swiss market.

9. Does your HTA review or inquire other international HTAs during the assessment process? If so, which ones are the usual partners?

The Swiss HTA program engages with various national and international HTA networks, such as the Swiss Network for Health Technology Assessment, the European Network for Health Technology Assessment and the International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment. The networks are used to share knowledge with other HTA agencies and to continuously develop HTA methodology.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

6. HTA Dossiers: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Have local authorities published recommendations and guidelines surrounding value assessment dossiers? (If yes please add link)

No official guidelines or recommendations are published. However, all pending and completed HTA projects are published on the FOPH’s website at https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/hta/hta-projekte.html (last visited on 19 January 2023). This allows potential submitters to get an understanding of the typical requirements of such submissions.

In addition, as from June 2022, the FOPH publishes a HTA Newsletter at https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/hta/hta_newsletterarchiv1.html (last visited on 19 January 2023).

2. Have local authorities published official guidelines surrounding the submission of value assessment dossiers? (If yes please add a link)

The FOPH has published a form at https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/versicherungen/krankenversicherung/krankenversicherung-leistungen-tarife/hta/hta-themeneingabe.html (last visited on 19 January 2023) where requests to assess a medical service or product with the HTA program can be filed.

3. Describe the overall process of preparing and submitting a HTA dossier in your country.

Anyone can propose for a medical service or product to be re-evaluated through HTA by using the topic submission form on the FOPH’s website (see link in question 3 above). The deadline for the submission of topics is 1 March of each year. After the deadline, the FMSC and the FDC will make recommendations on which topics should be addressed.

4. Describe the overall content of the HTA dossier in your country.

After the HTA has been conducted, the HTA dossier typically contains the following documents: the (final) HTA report, an HTA Supplement (which is a shorter version of the full report) and the HTA Protocol. In additions it can contain the Scoping Report and the Stakeholder Feedbacks on the final HTA Report, on the Protocol and on the Scoping Report.

5. Which are the questions to focus on when preparing a HTA dossier in your country?

HTA topics should ideally contain some amount of controversy regarding the efficacy or safety of the service or product. In addition, there must be a certain budgetary relevance to the service or product. The proposed improvement should further be feasible. The focus also needs to be laid on the benefits of the possible regulatory measures with regards to the reimbursability of the product.

6. Which are the other strategic considerations to take into account when preparing a HTA dossier in your country?

Ideally, the submission should be accompanied by scientific evidence that supports the claims regarding efficacy, suitability or cost-effectiveness of the respective medicinal service or product. When submitting the FOPH’s form, there is an option to upload documents to that effect, e.g., scientific papers or journal articles.

In addition, it is recommended to carry out a detailed analysis of all stakeholders involved and their potential interests, e.g., manufacturers, health insurer associations, association of medical practitioners, etc.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

7. Data Requirements: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. In addition to the clinical data obtained through clinical studies please list the data required for:

a. Market approval

According to Art. 11 TPA, an application for marketing authorisation must contain all of the essential data and documents for its assessment, which are in particular:

- Name of the medicinal product;

- Name of the manufacturer and the distributor;

- Manufacturing process, composition, quality and stability of the medicinal product;

In addition, all the clinical data obtained in clinical studies must be provided, especially:

- Results of physical, chemical, pharmaceutical and biological or microbiological tests;

- Results of pharmacological and toxicological tests and clinical trials, including all results from trials in specific population groups;

- Therapeutic effects and undesirable effects;

- Labelling, information supplied about the medicinal product and the dispensing method as well as the method of administration;

- Assessment of the risks and, if necessary, a plan for their systematic recording, investigation and prevention (pharmacovigilance plan);

- Pediatric investigation plan

b. Pricing Decisions

For the details and the data of the pricing decision process, see above chapter IV. In addition, the following data is required for the evaluation of the external and internal referencing prices.

For the ERP, the authorization holder must provide the FOPH with the relevant price, in principle the ex-factory price, of the reference countries. To this effect, a confirmation of the price by the authorization holders of the reference countries, a government authority or an association must be enclosed (Art. 34c para. 1 OBHI).

For the IRP, the authorization holder must provide the FOPH with all data used for the comparison between the product under review and the similar medicinal products until February 15 of the review year (Art. 34f para. 2 OBHI).

c. Reimbursement Decisions

In order to be reimbursable, medicinal products and services must be included in the LS. According to Art. 30a OHCS, a request to the FOPH for inclusion of an original drug on the LS must basically include the following documents and confirmations:

- Expert Information on the drug;

- Market authorization decision by Swissmedic (or at least a pre-notification by Swissmedic on the upcoming decision to grant authorization);

- Key Facts, i.e., facts on dosage, scientific studies regarding efficacy, pricing etc.;

- ERP documents;

- Clinical overview;

- Three most important peer-reviewed clinical studies on the medicinal product;

- Epidemiological data from Switzerland on the illness to be treated with the medicinal product.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

8. Managed Entry Agreements: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Are there any Managed entry agreements in place in your country? (If so, please list them)

2. Describe the fundamentals of the Managed entry Agreement, its rationale and the process for implementing it.

3. When should this Managed Entry Agreement be considered?

4. Which are the specific requirements to implement the Managed Entry Agreement.

5. What is the potential impact on the product uptake?

6. What are the potential challenges associated with this Managed Entry Agreement?

[Questions 1-6 answered jointly:]

The FOPH may use managed entry agreements (MAE) as an instrument to accelerate the availability of promising, innovative medicines in the context of medical and economic uncertainty. The FOPH makes predominantly use of MAE regarding drugs for the treatment of cancer and immunosuppressive drugs.

In Switzerland, two types of MAE can be distinguished: financial-oriented and result-oriented MAE.

Financial-oriented MAE provide for discounts which are not correlated to the result of the treatment. There exist various discount-models. For example, discounts can be granted without any preconditions. Other discount-models provide for indication-based discounts for drugs with different applications. Another example of a discount is that the costs are reimbursed after a certain treatment period. This cost-sharing model makes sense when the application period is significantly prolonged for a minority of patients. Other cost-sharing models use “Capitation”, i.e., after a certain treatment period, the therapy is continued free of charge.

The discount rate granted under an MAE is often kept confidential. The health insurance companies will have to apply to the manufacturer and ask for the applicable discount rate in each individual case.

Under the result-oriented (pay-for-performance, P4P) MAE, the remuneration of the pharmaceutical product is made contingent on the efficacy of the product for the patient.

Another type of resulted-oriented MAE is CED (Coverage with Evidence Development). When the potential benefit of a medicinal product is not yet supported by sufficient evidence, the FOPH can limit in time the inclusion of the product to the LS and make the definitive inclusion contingent on that additional, supportive data will be collected within this timeframe (Art. 65 para. 5 HIO).

According to a recent study of pharmaLevers GmbH from 2020, commissioned by curafutura (an association of four Swiss health insurance companies), the cost-oriented models are predominant in Switzerland and have various advantages over the, result-oriented MAE, which are consequently less commonly used (https://curafutura.ch/app/uploads/200810_pharmaLevers_kostenintensive-Medikamente_Preis-Modelle.pdf).

In Switzerland, MAEs are not published. However, for every drug listed in the LS, the list contains a so-called “Limitatio”-column. Under this column, the reimbursability of the drug can be limited both in quantity and medical indications (Art. 73 HIO). When a MAE is concluded, some of its terms (though not all) are typically listed in the “Limitatio”-column of the specific drug in the LS.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

9. Public Procurement and Tendering: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Which are the main actors involved in public procurement and tendering?

The main actors involved are usually the awarding body on the one hand and a private tenderer on the other hand. For the question, which bodies are subject to the rules of procurement, see above chapter II question 7.

2. What are the main characteristics of the public procurement and tendering system?

Both under procurements of the federal administration, which are subject to the PPA, and under procurements of cantonal and municipal bodies, which fall under the inter-cantonal agreement on public procurement, there exist four different tender procedures:

- The open procedure (Art. 18 ICAPC, Art. 18 PPA): Under this procedure, a public call for tenders is launched and any tenderer may submit a tender (usually within a deadline of 40 days).

- The selective procedure (Art. 19 ICAPC, Art. 19 PPA): Under this procedure, interested tenderers may submit a request to take part in the tender. Only those tenderers selected by the awarding body can then submit a tender (usually within a deadline of 25 days).

- The call for bids procedure (Art. 20 ICAPC, Art. 20 PPA): Under this procedure, no public call for tenders is launched. The awarding body sends a direct request to a minimum of three tenderers, asking them to submit a tender.

- The private contract procedure (Art. 21 ICAPC, Art. 21 PPA): Under this procedure, no public call for tenders is launched. The awarding body awards a contract directly to a tenderer. This procedure is an exception, and the awarding body has to state the reasons why it chose this procedure.

For each tender procedure, different rules apply. Which procedure is applicable to a specific tender, depends on various factors:

- the legal framework which will apply (international treaties (WTO GPA), federal law (PPA), or cantonal and communal law (ICAPC));

- the type of the awarding body;

- the type of services;

- the contract amount of the services (thresholds).

In general, the procurement process must be transparent, objective and impartial. According to Art. 11 lit. ICAPC, the contracting authority must ensure the observance of the following principles: Providers must be treated equally and must not be discriminated against. The competition must be effective. The contracting authority must refrain from bidding rounds. Recusal rules must be observed. Occupational health and safety regulations and working conditions for employees must be observed. Women and men must be treated equally. Information provided by the bidders must be kept confidential.

Many tenders in Switzerland (both from the federal government and from cantonal or municipal awarding bodied) are published at www.simap.ch (last visited on 19 January 2023).

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

10. Expenditure Control and Cost-Containment Policies: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Please describe the main cost containment policies in place in your country and their fundamental principles:

a. Pricing and impact of generic/biosimilar approval

Based on a price comparison with 15 reference countries (containing among others, all of the 9 countries which are used in Switzerland for the ERP), the Swiss Price Council (see below under question 1 e) has noticed in 2021 that generics and biosimilars in Switzerland are more than twice as expensive (+165%) (https://www.preisueberwacher.admin.ch/dam/pue/de/dokumente/newsletter/Newsletter_02_21_d.pdf.download.pdf/Newsletter_02_21_d.pdf). The Federal Council has recognized the problem and proposed the introduction of a reference pricing system for medicinal products with the aim to reduce costs in this area. Under the proposed system, the FOPH would have fixed a maximum price which insurers would have to pay for generics and biosimilars. If a generic or biosimilar were to be sold for a higher price, the difference would have had to be borne by the patient. However, this proposal was rejected by the Swiss Parliament.

b. Clawback/Payback/Discounts/Rebates

The respective policies in Switzerland are governed by the principles of integrity and transparency. In principle, all discounts granted on purchases of medicinal products must be specified on the receipts and invoices as well as on the accounts of both the seller and the purchaser and must be disclosed to the competent authorities on request (Art. 56 TPA). Service providers are further obliged to pass on price discounts and reimbursements granted to them, to patients or insurers.

Additionally, there are measures taken to prevent kickbacks. To that end, pursuant to Art. 55 TPA, a person who prescribes, dispenses, uses, or purchases prescription-only medicinal products, or an organization that employs such persons, may not solicit, be promised or accept any undue advantage for themselves or for the benefit of a third party. Equally, such persons may not offer, promise or grant any undue advantage. A violation of this prohibition is a criminal offence (Art. 86 para. 1 lit. h TPA).

c. Existence of Price/Volume agreements in the frame of public tendering

There is no specific regulation with regards to price/volume agreements in the frame of public tendering. The general rules of Swiss procurement law apply (see above chapter II. question 7 and chapter X). If specific price/volume agreements between manufacturers and payers include discounts, the aforementioned requirements regarding transparency and integrity must be observed.

d. Existence of price freezes and cuts

If the average costs per insured person and year in compulsory healthcare insurance for outpatient or inpatient treatment increase twice as much as the general price and wage development, Art. 55 HIA allows the competent authority (either on a federal or cantonal level) to prohibit the increase of rates or prices for all or certain services. As far as can be seen, no such price freezes are currently in place.

e. Post-launch monitoring of prescriptions/sales

Data on drug sales is collected by Interpharma, a private association of Switzerland’s research-based pharmaceutical industry. In its annual report, statistics and discuss trends regarding the pharmaceutical market in Switzerland are published (https://www.interpharma.ch/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/20220325_iph_Jahresbericht_2021_e_web-1.pdf).

Further, prices of medicinal products and services are monitored by the Swiss Price Council (“Preisüberwacher”) according to Art. 4 of the Price Monitoring Act (PMA; Preisüberwachungsgesetz, SR 942.20). The Price Council is a federal institution which advocates for consumer interests. It cooperates with the Swiss Competition Commission (Art. 5 para. 2 PMA). The PMA applies to competition agreements and to companies with strong market power, such as pharmaceutical companies (Art. 2 PMA).

The Price Council can react to abusive prices of drugs by seeking conciliation with the manufacturer (Art. 9 PMA). Further, it can give recommendations to the FOPH, to decline a requested or intended price increase in whole or in part or to reduce an abusively maintained price (Art. 14 para. 1 and 15 para. 2bis PMA). If the FOPH does not follow the recommendation of the Price Council, it must state its reasons for doing so (Art. 14 para. 2 and 15 para. 2ter PMA).

Prices of health products and services in Switzerland are regularly scrutinized by the Price Council. The Price Council periodically publishes comparisons of Swiss drug prices with German ones. It regularly issues recommendations about policy tools likely to lower drugs prices in Switzerland, which it has judged excessive.

f. Existence of Generic Substitution Policies

Pharmacists can replace original drugs that are listed on the LS with generics from the LS, unless the prescribing medical practitioner (physician or chiropractor) expressly requests for the original drug to be dispensed (Art. 52a HIA).

g. At prescriber level

According to Art. 23 TPA, medicines are categorized in different dispensing categories. Many Swiss cantons allow physicians to dispense all or certain medicinal products themselves, without the need for patients to obtain them from a pharmacy. Studies have shown that in cantons with such self-dispensing, the average cost of medicines per insured person is up to 30% lower than in other cantons.

h. At retail level

The aforementioned authorization for pharmacists to substitute original drugs with generics is an effective cost containment policy at the retail level. The Federal Council intends to implement further measures at pharmacy level to contain healthcare costs. In particular, the range of services that pharmacies may provide at the expense of the mandatory health insurance shall be limited.

2. Are there any other policies in place aiming at cost control via incentive programs targeting the different actors (pharma companies, wholesalers, retailers, prescribers etc.)?

There are several smaller policies with the aim of cost-containment that entered into force recently or will enter into force in the years to come; for example the obligation for service providers to automatically provide insured persons with an invoice or the fixation of a standardized rate for outpatient treatment.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

11. Essential Drug List: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. Has an essential or priority drug list been published in your country? (If so provide the link)

Yes, Switzerland publishes such a list in the annex to the ordinance on the Essential Human Medicines Reporting Office (EHMROO; Verordnung über die Meldestelle für lebenswichtige Humanarzneimittel, SR 531.215.32). It can be found at https://www.fedlex.admin.ch/eli/cc/2015/544/de (last visited on 19 January 2023).

2. If so, what is the impact/consequences of a drug being published on the EDL/PDL:

a. In terms of market approval

If a therapeutically important medicinal product authorized in Switzerland is not available for a limited period of time due to a bottleneck in supply (stock-out situation), the marketing authorization holder may submit an application for the temporary marketing of the identical preparation (qualitative and quantitative composition) in a foreign presentation on the basis of Art. 9b TPA. The application for temporary placing on the market may be approved, if (1) the availability of the medicinal product is therapeutically important, (2) no increased risk regarding the safety of the medicinal product must be assumed, and (3) no equivalent alternative preparation is available for this medicinal product in Switzerland.

b. In terms of reimbursement

There are no reimbursement consequences specifically in place for essential drugs.

c. In terms of pricing

According to the Report of the FOPH “Supply shortages of human medicines in Switzerland: Situational analysis and improvement measures to be reviews” from 1 February 2022 (https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/en/dokumente/biomed/heilmittel/bericht-sicherheit-mediversorgung.pdf.download.pdf/bericht-sicherheit-mediversorgung-en.pdf), measures for price reductions are associated with the risk of provoking market withdrawals due to inadequate profitability and thereby accentuating supply shortages. Therefore, as part of the triennial review of the listing requirements for the years 2017–2019, a price reduction was waived for reasons of security of supply for a total of 15 medicines at the request of the marketing authorization holders. The price reduction was reduced in one case.

d. In terms of value assessment and pharmacoeconomic requirements

The active substances listed in the annex to the EHMROO are evaluated by taking into account the medical necessity (vitality) and the supply risk (supply chain, market shares, past supply disruptions) of the individual product groups. Since supply chain risk assessment is an important component in the evaluation, it is inadmissible to conclude that an active ingredient not listed in the Annex is not vital. A vital agent that has been assessed as not critical to the supply chain is not subject to the reporting requirement of the stakeholders (see question 3 below).

3. Do value assessment and pharmacoeconomic data play a role in terms of access to the list?

With regard to the issue of safety in the supply of medicines, the Essential Human Medicines Reporting Office makes a decisive contribution to securing access to medicines in the event of disruptions in the supply chain. According to Art. 3 para. 2 EHMROO, marketing authorization holders are obliged to report supply shortages or interruptions of presumably 14 days or more in the supply of essential medicinal products for a specific dosage strength.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

12. Orphan Drugs: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. What is the definition of an orphan drug in your country?

According to Art. 4 para. 1 lit. adecies TPA, an orphan drug is a medical product for human use for which it has been proven either (1) that it is indicated for the diagnosis, prevention or treatment of a life-threatening or chronically debilitating disease, which affects no more than five in ten thousand people in Switzerland at the time of submission of the application for marketing authorization, or (2) that its active substances have been granted the status of important medical products intended to treat rare diseases by another country with an equivalent system of drug control.

2. Describe the pricing process of orphan drugs in your country.

The prices of reimbursable medicines are determined by the FOPH. The pricing process for orphan drugs does not differ from the standard pricing process described in chapter IV above.

3. Describe the reimbursement process of orphan drugs in your country.

To be reimbursable, generally, orphan drugs must, like other drugs, be included on the LS. For orphan drugs, a quick inclusion is typically of the essence. The request to the FOPH for inclusion on the LS can be submitted parallel to the request to Swissmedic for market authorization. After market authorization has been granted and provided that the WZW-criteria are fulfilled, the FOPH should grant the inclusion on the LS within 60 days (Art. 31b OHCS). However, in the Swiss parliament it was criticized that in practice, the inclusion of orphan drugs to the LS takes much longer or is not granted at all. In fact, only a small percentage of the existing and authorized orphan drugs in Switzerland has been included to the LS.

If an orphan drug has not been included in the LS, it can still be exceptionally reimbursed according to the rules on “reimbursement in individual cases” (Art. 71a – 71d HIO). Particularly relevant is Art. 71b para. 1 HIO, which grants reimbursability under the same conditions as for the off-label use of (normal) drugs, i.e., under the condition that the application of the drug is expected to bring a great therapeutic benefit against a disease which may have a fatal outcome or lead to severe or chronic problem for the insured person, and that there are no therapeutic alternatives (Art. 71a para. 1 letter b HIO). However, the Federal Supreme Court has clarified that orphan drugs, too, must meet the WZW-criteria of efficacy, suitability and cost-effectiveness (BGE 136 V 395, E. 6.5). Hence, even under the rules of “reimbursement in individual cases” of the HIO, orphan drugs which are not cost-effective (i.e., too expensive) will not be reimbursed.

Other than the clinical studies required, do the data and studies required for the pricing and reimbursement of orphan drugs differ from that of other drugs?

No, in general, the same WZW-criteria set out in Art. 32 HIA as for normal drugs (see above chapter III question 3) must be fulfilled for the pricing and reimbursement of orphan drugs.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

13. Vaccines: Switzerland

Join industry executives in staying informed on the market access and HTA process in Switzerland.

1. What is the definition of a vaccine in your country?

In Switzerland, most of the regulations related to vaccines are contained in the Federal Act on Controlling Communicable Human Diseases (EpidA; Epidemiengesetz, EpG, SR. 818.101) and in the Federal Ordiance on Controlling Communicable Human Diseases (EpidO; Epidemienverordnung, EpV, SR. 818.101.1). The legislation contains no legal definition of vaccines.

According to Art. 20 para. 1 EpidA, the FOPH – in collaboration with the Federal Commission for Matters of Vaccination (FVC) – develops and publishes a national vaccination plan. The plan includes immunization recommendations to protect the population, specific groups of persons at increased risk of infection, transmission, or complications, and individuals (Art. 32 para. 1 EpidO).

Further, the plan describes the vaccinations and vaccination schedules and contains information on the age suitable for vaccination, the number of vaccination doses, the intervals between vaccinations, and follow-up vaccinations (Art. 32 para 2 lit. a EpidO).

Physicians and other health professionals contribute to the implementation of the national vaccination plan as part of their work (Art. 20 para. 2 EpidA). The cantons play a supporting role in this process (Art. 21 EpidA).

The vaccination plan can be found at www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/gesund-leben/gesundheitsfoerderung-und-praevention/impfungen-prophylaxe/schweizerischer-impfplan.html (last visited on 19 January 2023).

2. What are the classifications of vaccines in your country?

Vaccinations can be divided into mandatory, recommended, and voluntary vaccinations. In cases of significant risk, cantons may declare a vaccination mandatory for populations at risk, persons particularly exposed, and persons engaged in certain activities (Art. 22 EpidA).

According to Art. 32 para. 2 lit. b EpidO, the national vaccination plan shall divide the recommended vaccines into three categories:

- Recommended basic vaccinations designed to protect individual and public health;

- Recommended supplementary vaccinations which provide individual protection against defined health risks;

- Recommended vaccinations for risk groups for which the vaccination is considered beneficial.

Regarding the (chemical or biological) mode of action, most of the vaccines, which are currently approved by Swissmedic, fall into one of the following categories: mRNA vaccines, viral vector vaccines and protein-based vaccines.

3. Describe the pricing process for vaccines in your country (based on their classifications).

The price of vaccines which are included in the LS is defined by the FOPH. In this regard, the pricing process does not differ from the pricing process of other pharmaceutical products which are included in the LS, described in chapter III and IV above.

Otherwise, the price may be set in a contractual arrangement between the manufacturer and the canton (e.g., in case that the vaccine is administered by a cantonal program).

4. Describe the reimbursement approval process for vaccines in your country (based on their classifications).

According to Art. 26 HIA, the compulsory health insurance covers the costs of precautionary measures in favor of insured persons who are at increased risk. Under this general rule, vaccines are reimbursable, if the following requirements are met:

- The vaccine is officially recommended by the FOPH, either in the national vaccination plan or in the FOPH-Bulletin;

- The vaccine is approved by Swissmedic (for the target group recommended by the FOPH);

- The vaccine was included into the list of Art. 12a OHCS as a reimbursable

As a result, vaccines which are not officially recommended for the general population (such as malaria and Hepatitis A+B prophylaxis in case of travel, or the yearly vaccination against the influenza virus for persons which have no increased risk of complications), are not reimbursable.

5. Other than the clinical studies required, do the data and studies required for the pricing and reimbursement of vaccines differ from that of other drugs?

For the systematic evaluation of whether a vaccination should be recommended (only recommended vaccinations are reimbursed, see above question 4), FVC and FOPH follow the “Criteria for the evaluation of new vaccines for the formulation of nationwide recommendations” (https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/i-und-b/ekif/analyserahmen-ekif.pdf.download.pdf/analyserahmen-ekif-de.pdf). These criteria are a Swiss-adjusted version of the analytical framework for immunization program in Quebec[1] and contain the following questions which need to be considered and discussed before a vaccine is officially recommended by the FOPH:

- Does the burden of disease justify making a vaccination recommendation?

- Do the characteristics of the vaccine allow an effective vaccination recommendation to be made?

- Does the proposed strategy(s) achieve the goal pursued by the vaccination recommendation?

- Is the cost-benefit ratio of the strategies acceptable and comparable to other health interventions?

- Is there an increased demand for a vaccination recommendation?

- Would such a vaccination recommendation meet with high acceptance?

- Can the vaccination recommendation be implemented?

- Can the various aspects of the recommendation be evaluated?

- Are there important open questions that have an impact on the implementation of the recommendation?

- Does the recommendation ensure equal access to vaccination for all target groups?

- Is the recommendation compatible with existing or planned Swiss and international recommendations?