The Pharma Legal Handbook: The Netherlands

Ready to tap into the EUR 4.7 billion Dutch pharma market? The Pharma Legal Handbook: The Netherlands is your key to unlocking this strategically positioned and flourishing market.The Netherlands isn’t just about a robust pharma market; it’s a hub of top-notch institutions, including the European Medicines Agency, world-class healthcare, and a thriving start-up culture. Add to that a highly educated workforce, tax incentives, and innovation grants, and you’ve got a recipe for success.

Prepared with Houthoff, a top-tier Dutch law firm.

October 2023

1. Regulatory, Pricing and Reimbursement: The Netherlands

1. What are the regulatory authorities with jurisdiction over drugs, biologicals, and medical devices in your country?

Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (Ministerie van Volksgezondheid, Welzijn en Sport)

The policy and regulation of drugs (‘medicinal products’), biologicals and medical devices falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. The Ministry has the primary responsibility for the Dutch healthcare system. It has delegated most of its executive and supervisory tasks to governmental bodies.

Medicines Evaluation Board (College ter Beoordeling van Geneesmiddelen) (“MEB“)

The MEB is the governmental body that is responsible for the assessment of medicinal products, the registration of medicinal products, the issuing of marketing authorizations and the monitoring of adverse reactions and risks (i.e. pharmacovigilance).

Farmatec

Farmatec is part of the Central Information Unit on Healthcare Professions (Centraal Informatiepunt Beroepen Gezondheidszorg, (CIBG)), which is an implementing organization of the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Farmatec’s responsibilities include, the granting of pharmaceutical licenses (i.e. wholesale and manufacturing permits), the registration of certain medical devices, the setting of maximum prices for medicinal products, the issuing of Certificates of Pharmaceutical Products (CPP) for the export of pharmaceutical products, and the granting of exemptions for the marketing of opioid drugs.

Health and Youth Care Inspectorate (Inspectie Gezondheid en Jeudzorg, (IGJ)) (“Inspectorate“)

The Inspectorate is generally responsible for supervising compliance with the regulatory framework. The Inspectorate enforces the regulatory requirements concerning the safety of medical devices as well as medicinal products. Its tasks include the supervision of the ‘Good Practices’ throughout the supply chain, pharmacovigilance, the monitoring of adherence to the registration and authorization requirements, product recalls, and the requirements regarding inducement, transparency and marketing. However, responsibility for supervising compliance with the regulatory framework within the armed forces lies with the Ministry of Defense. Supervision is carried out by a military-medical inspection body. The Ministry of Transport and Water Management has primary responsibility for the requirements concerning the provision of medicinal products on board commercial shipping vessels. The Maritime Division of the Human Environment and Transport Inspectorate (Inspectie Leefomgeving en Transport) is tasked with the supervision and enforcement of these requirements.

Other

The Foundation for the Code for Pharmaceutical Advertising (Stichting Code Geneesmiddelenreclame (CGR)) lays down rules of conduct for prescription drug advertising and cooperation between healthcare providers and pharmaceutical companies.

The Healthcare Transparency Register Foundation (Stichting Transparantieregister Zorg) is an implementing organization that ensures the disclosure of financial relationships between healthcare providers and industry in a central register, the Healthcare Transparency Register (Transparantieregister Zorg). The Healthcare Transparency Register includes information provided by companies, healthcare providers and healthcare institutions pursuant to the Code of Conduct for Medical Devices (Gedragscode Medische Hulpmiddelen) (see further Question 2 of this Chapter) and the Code of Conduct for Pharmaceutical Advertising (Gedragscode Geneesmiddelenreclame) (see further Chapter 3, Question 17).

2. What is the regulatory framework for the authorization, pricing, and reimbursement of drugs, biologicals, and medical devices?

Drugs (medicinal products)

The Medicines Act (Geneesmiddelenwet) contains the requirements concerning the production and marketing of medicinal products and also provides for the implementation in Dutch law of Directive (EU) 2001/83 on medicinal products for human use. Implementing measures follow from the Medicines Act Regulation (Regeling Geneesmiddelenwet) and the Medicines Act Decree (Besluit Geneesmiddelenwet). The Medicine Prices Act (Regeling maximumprijzen geneesmiddelen) sets maximum allowable prices for medicinal products in the Netherlands. The rules on the reimbursement of medicinal products are tied in with the national health insurance system.

Biologicals

Biologicals are included in the Medicines Act. Therefore, biologicals are not addressed separately in the remainder of this contribution unless they are treated differently.

Medical devices

Regulation (EU) 2017/745 on medical devices (“MDR“) and Regulation (EU) 2017/746 on in vitro diagnostic medical devices (“IVDR“) apply directly to medical devices produced, placed on the market and offered to patients in the Netherlands (including via e-commerce). These regulations have direct effect and do not require transposition into Dutch law. The Medical Devices Implementing Regulation (Regeling medische hulpmiddelen) sets language requirements and designates competent authorities for the implementation of the MDR and the IVDR. Additional national requirements and requirements relating to the application of these regulations are laid down in the Medical Devices Act (Wet medische hulpmiddelen). The implementing rules relating to this act concerning medical devices are laid down in the Medical Devices Decree (Besluit medische hulpmiddelen) and the implementing rules concerning in vitro diagnostics are laid down in the In Vitro Diagnostic Medical Devices Decree (Besluit in-vitro diagnostica).

Moreover, a private Code of Conduct for medical devices aims to elaborate, in addition to the applicable legislation, on a careful, transparent and responsible relationship between suppliers of medical devices and the parties involved in the decision-making about their purchase and/or application. A sizeable number of medical device suppliers adhere to this code.

Reimbursement

Most medicinal products and medicinal devices are reimbursed on the basis of either the Healthcare Insurance Act (Zorgverzekeringswet) or the Long-Term Care Act (Wet langdurige zorg) and the accompanying regulations, e.g. the Healthcare Insurance Regulation (Regeling Zorgverzekering) and the Long-Term Care Regulation (Regeling langdurige zorg) (see further Questions 10 to 13 of this Chapter).

3. What are the steps to obtain authorization to develop, test, and market a product?

Drugs (medicinal products)

Development and testing

Authorization for new clinical trials (drug research) must be obtained from the Member State in which the drug research takes place, via the procedure prescribed by the Clinical Trial Regulation (EU) 536/2014 (“CTR“). The CTR entered into force on 31 January 2022 and replaces the Clinical Trials Directive 2001/20/EC. The Netherlands had implemented this Directive in the Medical Research (Human Subjects) Act (Wet medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen, ”MRA”). With the entry into force of the CTR, Directive 2001/20/EC was repealed, as well as Article 5a of the MRA, which specifically concerned drug research. From 31 January 2022 onwards, a three-year transition period applies for drug studies approved under the Directive 2001/20/EC and the MRA to the CTR. As from 31 January 2023, the CTR applies to all new applications for drug research. Under the CTR, a single procedure for submission, assessment and conduct of drug research applies to all drug studies (national and multinational) conducted in the European Economic Area (EEA). Clinical trial applications must be submitted via the Clinical Trials Information System (“CTIS“), which is maintained by the European Medicines Agency (“EMA“). The authorization and oversight of clinical trials remains the responsibility of the Member States. The CTIS is maintained by the EMA and is the single entry point for submitting the clinical trial application in the EU. From 31 January 2025 onwards, all current drug studies that have been approved under the old framework must comply with the CTR requirements as well. The MRA requirements remain applicable to other forms of medical research that do not fall within the scope of the CTR (see further Chapter 2).

Manufacturing

Dutch law prohibits the preparation, import, stocking, offer for sale, delivery, export or otherwise bringing of products containing active pharmaceutical ingredients (“APIs“) into Dutch territory, or taking them out of Dutch territory, or the operation of a wholesale business in APIs, without prior registration (Article 38 Medicines Act). In practice, this registration obligation is implemented via a permit requirement. Permits are issued by Farmatec. Two different permits exist:

- A wholesale permit for the sourcing of APIs from an EEA country;

- A manufacturing permit for the preparation and procurement of medicinal products. In this regard, packaging and labeling are also considered preparatory acts for which a manufacturing permit is required. The sourcing of APIs from outside the EEA also requires a manufacturing permit. Finally, an additional permit is required for the preparation of medicinal products involving human tissue collected for human treatment, on the basis of the Safety and Quality of Body Materials Act (Wet veiligheid en kwaliteit lichaamsmateriaal).

Moreover, the ‘Good Practices’ must be adhered to throughout the supply chain for medicinal products that are destined for the EU market: the Good Laboratory Practices (“GLP“), Good Manufacturing Practices (“GMP“) and Good Distribution Practices (“GDP“) prescribe quality and safety standards and procedures for different stages of the supply chain.

Marketing authorization

Every medicinal product marketed in the Netherlands must have marketing authorization (“MA“) issued by a competent authority (Article 1(1)(III) Medicines Act). To obtain MA, an application must be submitted together with information and documents regarding the quality, safety and efficacy of the medicinal product. The competent authority for the EU, the EMA, based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, or the competent authority for the Netherlands, the MEB, will carry out a benefit/risk assessment.

There are a number of exceptions from the requirement of MA, which are listed under (a) to (h) of Article 40 Medicines Act.

Procedure

In principle, applicants may choose one of the following procedures when submitting their application for MA, depending on the type of medicinal product and its intended marketing:

- the centralized procedurefor an MA valid in the EU;

- the decentralized procedurefor the marketing of the medicinal product on the markets of several EU member states at once by submitting an application to one Reference Member State (RMS);

- the national procedurefor an MA that is valid only in the Netherlands;

- the mutual recognition procedure(MRP) for an MA on the basis of recognition of the assessment by the RMS;

The application must be submitted by a natural person or legal entity established in the Netherlands or in another EU Member State. The EMA is responsible for the granting of marketing authorizations through the centralized procedure. The MEB is responsible for the granting of marketing authorizations through the decentralized procedure, the national procedure and the mutual recognition procedure.

The centralized procedure leads to one MA valid throughout the EU, which is its main advantage. Applicants must submit their application file to the EMA for assessment by the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). The centralized procedure is compulsory for human medicinal products containing a new active substance to treat, medicinal products derived from biotechnology processes, advanced-therapy medicinal products, orphan medicinal products, and veterinary medicinal products for use as growth or yield enhancers.

The decentralized procedure may be chosen if the applicant does not yet have an MA in any EU Member State or EEA State. It enables MA to be obtained for several EU/EEA states at once. The applicant may request one state to be the Reference Member State (RMS). An applicant opting for the Netherlands as RMS may use the MEB planning tool to select a time slot for the procedure.

The national procedure is available only if the centralized procedure is not required and if the applicant has not yet obtained an MA or submitted an MA application in another EU/EEA Member State. An MA obtained via the national procedure covers the Netherlands’ market only. The national procedure at the MEB may also serve as the first phase of an MRP if the Netherlands is going to act as the RMS in such procedure. In the MRP, the applicant applies for an MA in an EU/EEA Member State on the basis of the MA issued by the RMS. The RMS’s assessment forms the basis for the assessment in the other EU/EEA Member States.

If an application concerns a medicinal product for which the file is identical to that of a product that is already authorized in the Netherlands, the MEB can forego a full evaluation and issue a ‘duplex’ MA. In principle, this procedure can be followed for a medicinal product that fulfills both of the following: (i) it has an approved Risk Management Plan (RMP); and (ii) it received MA no more than 5 years ago or completed an MRP with the Netherlands as its RMS. The duplex procedure can be followed for medicinal products authorized more than five years ago if a specific set of supplementary conditions is fulfilled. The supplementary conditions aim to guarantee that the duplex and reference product remain identical.

There are several situations in which an applicant does not need to follow the standard application procedure. The main circumstances in which this is the case are listed below.

Abridged procedure:

- in certain cases, applicants are not obliged to submit the results of pre-clinical and clinical trials (Article 42(5) Medicines Act), for example as regards generic versions of medicinal products (see Question 6 of this Chapter).

- In the case of medicinal product shortages, an abridged procedure can also be applied under certain circumstances (Article 3.17a Medicines Act Regulation).

Other exceptions or additional requirements:

- In exceptional circumstances, the competent authority can grant a conditional marketing authorization.

- The MEB can allow the marketing of non-authorized medicinal products for compassionate use.

- For orphan medicinal products, market exclusivity applies after they receive an MA. For a period of ten years (which period can be extended by two years), no other MA may be considered or granted for the same therapeutic indication in respect of a similar medicinal product.

- Medicinal products prepared through magistral preparation by apothecaries are excluded from the authorization obligation.

- The MEB applies stricter requirements to the evaluation of medicinal products for children (pediatric use).

Medical devices

The MDR and the IVDR contain the conditions for placing medical devices on the market in any EU Member State.

Regarding the entity placing the medical device or in vitro diagnostic medical device on the market, the MDR and IVDR differentiate between manufacturers, importers, wholesalers and authorized representatives. If the manufacturer has its seat outside of the EU, an authorized representative must be designated that is ultimately responsible for communicating with the authorities and also liable in case of default.

The MDR divides medical devices into the following risk classes:

- Class I (low risk): products that are non-sterile or do not have a measuring function;

- Products of class Is: sterile medical devices;

- Products of class Im: medical devices with a measuring function;

- Devices of class Ir: reusable medicinal products;

- Class IIa (medium risk) and Class Iib (medium/high risk);

- Class III (high risk).

Development and testing

Clinical trials with medical devices must be notified to the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO), pursuant to the MRA (see further Chapter 2).

Marketing

Under European and Dutch law, there is no obligation to obtain an MA for medical devices and in vitro diagnostic devices. However, medical devices placed on the EU market must bear a CE marking, and manufacturers, or their authorized representative, are obliged to issue a declaration of conformity (“DoC“) before marketing a medical device. By issuing the DoC, the manufacturer acknowledges liability for the conformity of the medical device with the requirements of the MDR.

Conformity assessment

Class I medical devices are self-certified, which entails that the manufacturer itself may prepare a declaration of conformity with the MDR.

For medical devices that fall in Class IIa, IIb or III, a conformity assessment by an independent authority (“Notified Body“) is required for the CE marking of the product. If the Notified Body approves the product, the applicant will receive a CE certificate. The following three Notified Bodies have been appointed by the Dutch authorities: DEKRA Certification B.V., DARE!! Services B.V., and BSI Group The Netherlands B.V.

For certain high-risk devices, the Notified Body is required to consult an expert panel before issuing a CE certificate.

Registration

Before placing any medical device on the EU market, manufacturers located in the EU and authorized representatives of non-EU manufacturers may also be subject to registration requirements in EUDAMED, the online system developed by the European Commission for this purpose. If the relevant section of EUDAMED is not yet fully operational, manufacturers and authorized representatives located in the Netherlands must notify Farmatec of the device (via the online registration system NOTIS).

Netherlands-based manufacturers and authorized representatives of non-EU manufacturers are required to submit notifications to Farmatec in respect of medical devices and in vitro diagnostic medical devices belonging to specific risk classes:

- Class I medical devices must be registered in EUDAMED before placement on the market. If EUDAMED is not yet fully operational, the product must be registered in NOTIS. Existing notifications for Class I medical devices made under the MDR’s predecessor (Directive 93/42/EEC concerning medical devices) remain valid until 26 May 2024. Existing notifications must be entered into EUDAMED before that date to remain valid (or the NOTIS notification must be updated if EUDAMED is not yet fully operational).

- Custom-made medical devices within the meaning of Article 21 MDR must be registered in NOTIS (Article 2 Medicines Act Regulation). A list of matters that must be included in a notification is available on Farmatec’s website. The list includes address details, the means of identification of the device, a declaration that the device is exclusively intended for use by a specific patient or user, the specific characteristics of the product, and information on safety and performance.

- For medical devices that fall in Class IIa, IIb or III, notification is not required.

NOTIS cannot be accessed without a Level 2+ eRecognition token. ‘eRecognition’ is a digital tool for secure online communication between companies and Dutch government organizations. It is used for various affairs such as registration and permit applications. An eRecognition login token must be obtained from a private, recognized provider. A prerequisite for the use of eRecognition software is a registration number with the Dutch Chamber of Commerce. Therefore, the manufacturer or authorized representative must first ensure it is established in the Netherlands and entered in the commercial register of the Dutch Chamber of Commerce before it can initiate the required registration procedure.

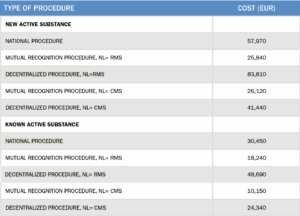

4. What are the approximate fees for each authorization?

Medicinal products

The fees for an MA application for a medicinal product are due from the moment of submission of the application and will not be refunded regardless of the outcome of the procedure. The fees charged by the MEB depend on the type of procedure and on the type of product. The MEB has published a full overview of the various fees on its website.

An overview of the application costs for the main categories is set out below (where RMS refers to Reference Member State and CMS refers to Concerned Member State):

The approximate fees payable for the examination of an application for medical device licence varies by the class of licence and the type of device, and range from $522 for Class II, $10,679 for Class III, to $25,955 for Class IV medical device applications.

Market authorizations for drugs are valid indefinitely, subject to their compliance with the Food and Drugs Act and its regulations.

SAP authorizations are valid only for maximum quantities of up to a six-month supply. Renewals can be ordered through the usual methods under the SAP.

Manufacturers of medical devices that are licenced for sale in Canada are required to inform Health Canada each year before November 1 that the information submitted with their licence application and any subsequent amendments have not changed. This is referred to as the licence renewal process. Manufacturers of licenced Class II, III and IV medical devices are charged an annual fee, payable at the time of licence renewal, for the right to sell their devices in Canada. The annual fee for the right to sell a licensed Class II, III or IV medical device in Canada is $394 as of April 1, 2022.

Persons holding an establishment licence (drug and device) also undergo a yearly review process, and must submit to the Minister, the information required in their original application each year. The licence holder will receive prior notification and failure to submit the review request will render the licence invalid.

The costs for amendments of an existing authorization are included in the annual fee, which amounts to EUR 1,900, or EUR 1,490 if the Netherlands serves as the RMS.

The MEB may suspend an MA if the annual fee is not paid in full in time, i.e. if the MA holder is in default under Dutch civil law (Article 6:81 Dutch Civil Code).

For the issuing of permits by Farmatec the following fees are due: for a manufacturing permit, an application fee of EUR 2,600 and an annual fee of EUR 3,200 (pro rata per month for the first year). For a wholesale permit, an application fee of EUR 1,700 and an annual fee of EUR 1,600.

Medical devices

If an assessment by a Notified Body is required, the manufacturer will bear the costs thereof. Notified bodies charge time-based or flat fees for the conformity assessment pursuant to the MDR, in accordance with standard lists made publicly available (Article 50 MDR and Article 46 IVDR).

Moreover, Article 111 MDR and Article 104 IVDR provide for the possibility of charging a fee for activities described in the regulations. On this basis, a fee is charged for the issuing of a certificate of free sale (outside of the EU) (Article 3 Medical Devices Implementing Regulation). Manufacturers or authorized representatives must pay a fee of EUR 62 per certificate and EUR 62 administration costs per invoice. Such certificate can be applied for via NOTIS.

A fee of EUR 200 applies for the notification to NOTIS of each individual product, regardless of whether the product is already registered in another EU Member State. No fee applies to product registration in EUDAMED. This fee does not include the cost of the eRecognition (see further Question 3 of this Chapter).

5. For how long are marketing authorizations/registrations valid? How are marketing authorizations/registrations renewed?

Medicinal products

In principle (unless a conditional marketing authorization as referred to in Article 45b Medicines Act is concerned), an MA for a medicinal product is valid for a period of five years from when it is first granted (Article 24(1) Directive 2001/83/EC). After five years, an authorization may be renewed at the request of the marketing authorization holder. The MEB will carry out a re-evaluation to determine whether the MA can be renewed, for which purpose the MA holder must submit a consolidated version of the file to the MEB, including changes made since the MA was granted and the review of suspected adverse reaction reports and periodic safety reports. The MA holder must do so at least nine months before the MA is due to expire. Renewal may be granted for an indefinite period, or for reasons of pharmacovigilance, for one more period of five years. The MA will be deemed to have lost its validity if the relevant medicinal product is not actually marketed for three consecutive years.

Medical devices

A DoC is valid indefinitely, but should be re-issued if significant changes to the medical device have been made. A CE certificate is valid for a maximum period of five years (Article 56 MDR).

6. How does the authorization process differ between brand-name products and generic products? Are there differences for local manufacturers versus foreign-owned manufacturers?

Authorization of generic products

For a generic product, the submission of a complete application file is not required; an applicant can apply for an abridged marketing procedure. The applicant is not required to provide results of pharmacological, toxicological and clinical tests if it is demonstrated that the product is a generic product (Article 42(5) Medicines Act). On this basis, the applicant may follow an abridged procedure with reference to the complete case file of the reference product. In evaluating the application, the MEB will verify whether the submitted product qualifies as a generic in comparison to the reference product.

In essence, the obligation to conduct pharmacological, toxicological and clinical tests that is part of the regular procedure is replaced by the obligation to demonstrate that the medicinal product is essentially equivalent to a medicinal product authorized not less than eight years prior to the date of the application by any EU Member State. That product is considered the reference medicinal product to the generic product. In the abridged procedure, the MEB will also evaluate the safety and effectiveness of the generic product.

The generic medicinal product may be marketed ten years after the grant of the MA for the reference medicinal product. This period can be extended by one year if the MA holder for the reference product has acquired a new pharmaceutical indication for which new pre-clinical and clinical studies have been conducted.

Authorization of brand-name products

For brand-name products, the procedure as set out under Question 3 of this Chapter applies.

Foreign-owned manufacturers

A manufacturer’s ownership is not decisive for the question of whether a medicinal product may be marketed in the Netherlands. Medicinal products for which an MA has been granted by the MEB, for which an MA issued by a different EU Member State has been recognized under the mutual recognition procedure, or for which MA has been granted by the Commission under the centralized procedure (see further Question 3 of this Chapter), may be placed on the Dutch market.

7. How are combination products (drug + drug, drug + biologic, drug + device, biologic + device, drug + biologic + device) regulated?

In principle, any substance or combination of substances intended to be administered, used or presented in any way as suitable for the treatment or medical diagnosis of a person is regarded as a medicinal product within the meaning of the Medicines Act (Article 1(1)(b) Medicines Act). This definition is in accordance with the definition of Directive (EU) 2001/83 on medicinal products for human use.

Products that combine a medicinal product or substance and a medical device are regulated under either the MDR or the Medicines Act, depending on the purpose of the product. If the medical device concerned incorporates, as an integral part, a substance that would in itself qualify as a medicinal product within the meaning of Directive (EU) 2001/83, but that primarily functions as and has the purpose of a medical device, the combination product is governed by the MDR. The Notified Body carrying out a conformity assessment of a medical device pursuant to the MDR or IVDR may request the MEB to advise on the quality, safety and beneficial properties of the integrated medicinal product (pursuant to Article 9(1)(h) Medicines Act). On the other hand, if the effect of the substance that qualifies as a medicinal product is most important, the combination product must be regarded as a medicinal product and the Medicines Act applies. The results of the assessment of the device part’s conformity with the relevant general safety and performance requirements pursuant to the MDR must be submitted in the MA procedure.

8. How is compliance with regulation monitored and evaluated? Is the regulatory regime comparable with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration or the European Medicines Agency expectations and requirements?

General supervision and enforcement

The Inspectorate, as the designated supervisory authority (see further Question 1), monitors the Dutch regulation of medicinal products and medical devices. To this end, it may carry out inspections and impose sanctions in cases of noncompliance. The Inspectorate also conducts periodic inspections of all drug manufacturers in the Netherlands, assessing whether the manufacturers comply with GMP and GDP (the Inspectorate usually combines GMP and GDP inspections). The Inspectorate may impose sanctions in cases of noncompliance. In principle, the Inspectorate publicly discloses enforcement documents, including inspection reports and sanction decisions (see further Question 9 of this Chapter).

Pharmacovigilance (medicinal products)

The requirements for pharmacovigilance are laid down in EU and national legislation and are further elaborated on in EMA’s good pharmacovigilance practices (GVP).

The MEB is the designated national competent authority for the coordination of pharmacovigilance in the Netherlands. It is responsible for the authorization and safety monitoring of medicinal products in the Netherlands (Article 76 Medicines Act).

With regard to its role in pharmacovigilance, the MEB is supported by the Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre ‘Lareb’, an independent foundation funded by the MEB and the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport. Patients and healthcare providers may report adverse drug reactions to Lareb via an online form. Lareb analyses reports of adverse drug reactions to identify risks associated with the use of medicinal products and reports its findings to the MEB for review.

The Inspectorate monitors compliance with the pharmacovigilance requirements by MA holders, and conducts inspections according to the national inspection program. It also carries out EU inspections in accordance with the EMA inspection program of central market authorization holders when the pharmacovigilance system master file (PSMF) is located in the Netherlands.

There are two types of inspections: routine inspections and unannounced inspections following a notification:

- routine inspections are scheduled in advance and usually focus on all elements of pharmacovigilance implementation; and

- inspections following a notification focus on specific elements.

For the national inspection program, the IGJ classifies MA holders according to their risk profile. This profile is generated through a pharmacovigilance questionnaire that MA holders fill out.

Regarding EU inspections, every EU MA holder should have a Pharmacovigilance System Master File (PSMF). This document contains all data and processes relevant to the marketing authorization holder’s pharmacovigilance system. This document must be registered in a European country. The Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) has drawn up a European Inspection Plan for this purpose.

As of 1 February 2019, all reports resulting from the national inspection procedure are published by the IGJ. If an inspection shows noncompliance with the pharmacovigilance requirements by an MA holder, the Inspectorate will draw up a draft report and give the healthcare provider the opportunity to submit comments within a limited timeframe. The Inspectorate will amend the report if necessary and circulate the final version. The Inspectorate will publicly disclose the report via its website at least two weeks after the healthcare provider has received the final report. The Inspectorate informs the MEB and other Member States of cases of noncompliance.

Medical devices

Pursuant to the Medical Devices Act, Inspectorate officials are authorized to carry out inspections of compliance with the rules on medical devices and inspections of sanction violations.

Manufacturers and authorized representatives must report any serious incidents and corrective actions (Field Safety Corrective Actions) relating to medical devices or in vitro diagnostic medical devices to the Inspectorate within strict deadlines in accordance with the MDR. The Inspectorate publishes safety warnings that have been reported to it on its website. Reports will have to be made through EUDAMED once it becomes fully functional.

Inducement

The Inspectorate also enforces the rules on inducement that apply to medicinal products and medical devices on the basis of Article 94 Medicines Act and Article 6 Medical Devices Act (see further Chapter 3, Question 8). The Inspectorate monitors compliance with the inducement rule in accordance with the respective policy rules: the Policy Rules for Inducements under the Medicines Act 2018 (Beleidsregels gunstbetoon Geneesmiddelenwet 2018) and the Policy Rules for Inducements under the Medical Devices Act (Beleidsregels gunstbetoon Wet medische hulpmiddelen).

9. What is the potential range of penalties for noncompliance?

Administrative fines

An administrative fine may be imposed for each individual case of noncompliance with the rules on medicinal products and/or on medical devices, up to a maximum of EUR 870,000, or, if higher, a fine not exceeding 10% of the undertaking’s turnover for the preceding financial year. The method of determining the fine for each individual offense, the rules for the imposition of the fine and the maximum amounts are set out in the Annexes to the Ministry of Public Health Welfare and Sport Policy Rules on Administrative Fines 2019 (Beleidsregels bestuurlijke boete Ministerie Volksgezondheid Welzijn en Sport 2019). The level of a fine imposed under these policy rules is determined on the basis of a number of factors: the gravity of the offense, the risk class of the product (in as far as medical devices are concerned), the seriousness of the offense, the presence of mitigating circumstances, the culpability of the offender, the size of the company and the risk of recidivism.

Periodic penalty payments

Depending on the specific offense, a penalty payment may be imposed in addition to an administrative fine. The annexes to the policy rules mentioned above specify for which offenses the option of imposing a penalty payment is available.

Public disclosure

The Inspectorate is under an obligation to publicly disclose reports and other information concerning its enforcement of healthcare regulations, such as decisions of Dutch administrative law (under Article 5:2 of the General Administrative Act (Algemene wet bestuursrecht)) to impose a sanction, or to conduct enhanced surveillance of a MA holder. This obligation is subject to a limited number of exceptions, such as decisions to impose criminal sanctions. If a healthcare provider wishes to object to disclosure it may apply to the interim relief judge for a preliminary injunction within two weeks of receiving the final report. The compulsory public disclosure follows from Article 44 to 44e of the Health Act (Gezondheidswet) and applies since 1 February 2019. As of that date, the Inspectorate publishes the information it is legally required to disclose. No prior balancing of interests takes place.

Inducement

For infringement of the inducement rules, the inspection usually imposes an administrative fine. This fine can be imposed on both the supplier of the medical device and the medical professional or institution that accepts the inducement. The amount of the fine is calculated in accordance with the policy rules mentioned above. The standard amount for a fine for infringement of the prohibition of inducement is EUR 150,000.

Criminal sanctions

If an infringement is also classified as a criminal offense, the Inspectorate will inform the public prosecutor of the case of noncompliance (Article 6 of the Ministry of Public Health Welfare and Sport Policy Rules on Administrative Fines 2019).

10. Is there a national healthcare system? If so, how is it administered and funded?

Introduction

The Netherlands has a private healthcare system that is heavily regulated and monitored by the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport and public authorities including the Dutch Healthcare Authority (Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit (“NZa“), the National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland) and the Inspectorate. Healthcare is provided via general practitioners, hospitals and other healthcare providers, who have to comply with a variety of rules and regulations on e.g. pricing, quality and certain medical standards.

In the Netherlands healthcare system, a distinction is made between cure and (long-term) care. The former is laid down in the Healthcare Insurance Act and is organized by (privatized) health insurers and financed on the basis of premiums and deductibles. The latter has its roots in the Long-Term Care Act; it is organized by a subsidiary of health insurers and financed by the government with designated funds received through taxation and income-dependent contributions. Some medical devices, e.g. wheelchairs and house adaptations, are financed by municipalities, based on the Social Support Act (Wet maatschappelijke ondersteuning). Depending on the individual situation, medicinal products and medical devices are reimbursed under one of these systems.

Basic health insurance

Dutch residents and employees have to take out basic healthcare insurance in accordance with the Healthcare Insurance Act. This type of healthcare makes up approximately 55% of the total healthcare costs in the Netherlands. Health insurers cannot refuse to provide basic insurance for any individual and there are certain restrictions in relation to the premiums charged for the insurance.

The Healthcare Insurance Act determines which care is eligible for reimbursement. Healthcare is mostly offered by contracted healthcare providers in kind. If insured individuals receive non-contracted care, insurers are not obliged to fully reimburse the costs. However, it is also possible to take out a more expensive insurance policy based on free choice of healthcare providers in which case non-contracted care is fully reimbursed as well. Academic hospitals receive additional contributions from the government, mainly for their academic activities. Specifically concerning medicinal products, only medicinal products included in the Drug Reimbursement System (Geneesmiddelenvergoedingssysteem, GVS) are covered (see further Question 13 of this Chapter).

Insurers conclude mostly annual contracts with healthcare providers to ensure their insured population has access to the basic care under the mandatory health insurance. Insurers receive monthly premiums and, depending on the health characteristics of the insured population, additional compensation from a special fund composed of designated taxation and income-dependent contributions. As of 2023, there are approximately 10 players in the Netherlands’ healthcare market, with a much larger number of insurance brands offering basic healthcare insurance.

Long-term care

Those insured are automatically covered for long-term care under the Long-Term Care Act. Long-term care makes up almost 33% of the total cost for healthcare. The coverage is paid fully by the government with money raised through designated taxation and income-dependent contributions. Subsidiaries of health insurers are responsible for organizing the long-term care and provide either the care or a payment for care contracted directly by the insured (via the ‘personal care budget’ (persoonsgebonden budget)). Whilst the long-term subsidiary has a duty of care towards its own insureds, for reasons of efficiency the long-term care is organized by one of the subsidiaries per region care administration offices (zorgkantoren). Both the subsidiaries and the care administration offices are fully reimbursed for the costs they make to organize long-term care.

11. How does the government (or public) healthcare system function with private sector healthcare?

Insurance companies offering basic health insurance usually offer various healthcare products that are complementary to the mandatory basic healthcare insurance. Such additional healthcare insurance is not governed by the Healthcare Insurance Act. As such, complementary healthcare insurance is not subject to an acceptance obligation. The health insurer determines the content, conditions and reimbursements of the supplementary insurance. Healthcare providers do have to comply with certain general rules and regulations, for example as regards quality.

12. Are prices of drugs and devices regulated and, if so, how?

Central government does not set fixed prices for medicinal products and devices. However, the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport does set maximum allowable prices for medicinal products twice a year by ministerial regulation in accordance with the Medicine Prices Act (Wet Geneesmiddelenprijzen). The Medicine Prices Act divides comparable medicinal products (intramural as well as extramural) in product groups based on API, strength and pharmaceutical form. The maximum allowable price for these product groups is then set on the basis of a comparison with the prices in four reference countries: Belgium, France, Norway and the United Kingdom. Germany was replaced by Norway as reference country for setting maximum prices by an amendment of the Act in April 2020, the primary reason being that prices in Germany were above the average for the Netherlands (and of the European Union as a whole) whereas the prices in Norway were significantly lower than in the Netherlands. At the same time, the social security system and level of healthcare were regarded as similar to the Netherlands. This amendment thus led to a decline in maximum prices in the subsequent evaluations of the maximum price.

The maximum price set for each registered medicinal product (brand name or generic), per quantity and pharmaceutical form, is included in the Annex to the Medicine Prices Act. The sale of a medicinal product at a price higher than the set maximum price, to end-users as well as to authorized suppliers of medicinal products to end users, is prohibited (Article 4 Medicine Prices Act). Sellers are under a legal obligation (Article 5 Medicine Prices Act) to keep records showing that they act in the conformity with the maximum price. Within these limits, the price may differ per health insurer, since wholesale margins are not fixed but rather are based on individual agreements resulting from negotiations. Health insurers negotiate vis-à-vis the manufacturer or wholesale distributor of the medicinal product on the one hand, and the pharmacists that dispense medicinal products to patients on the other.

13. How are drugs and devices used by patients paid for? What roles do public and private payers play?

Medicinal products are reimbursed or paid for directly by the health insurer (or zorgkantoor in the case of long-term care), unless the drug is not covered by the patient’s healthcare insurance or if the care falls under the compulsory deductible of the patient’s healthcare insurance, in which case the patient must pay for the drug themselves.

Moreover, Dutch health insurers will only reimburse a registered drug if it is included in the Drug Reimbursement System. The Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, and the National Health Care Institute decide together which medicinal products fall within the basic healthcare insurance coverage and whether they are either fully or partially reimbursable under the Drug Reimbursement System. The medicinal products included in the Drug Reimbursement System are divided in two lists which are included in Annex 1A and 1B of the Healthcare Insurance Regulation. Medicinal products which are interchangeable with each other are clustered and placed in Annex 1A. Medicinal products included in Annex 1A have a reimbursement limit. If the price exceeds this limit, the insured will have to pay for the additional sum. Medicinal products which are not interchangeable are placed in Annex 1B. No reimbursement limit applies to medicinal products included in this annex. Annex 2 of this regulation contains medicinal products which are only reimbursed under special conditions, such as for certain indications or patient groups. Over-the-Counter (OTC) products are not reimbursable.

Health insurers also generally only reimburse the cheapest version of a medicinal product containing the same active ingredient as the branded product. Health insurers are obliged to cover (at least) one variant per active ingredient. The preferential policy of the health insurer states for each active ingredient which variant is covered by the healthcare insurance. A different (more costly) variant will only be reimbursed by the health insurer if a healthcare practitioner has issued a statement that the patient requires a specific different variant for medical reasons.

The introduction of new medicinal products in the Netherlands takes a relatively long time as a price agreement has to be negotiated with the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport before a medicinal product can be included in the Drug Reimbursement System. The supply of new medicinal products before such agreement is concluded is not reimbursed. However, pharmaceutical companies sometimes choose to make medicinal products available to patients (without receiving reimbursement) in anticipation of inclusion in the Drug Reimbursement System and pending an agreement on price and reimbursement.

14. Who dispenses drugs and devices to patients and how are those dispensers compensated?

Pharmacists dispense medicinal products on the basis of a prescription and must abide by legal rules and professional standards in doing so (see further Question 15 of this Chapter). Pharmacists may not pay more than the set maximum prices. When buying in medicinal products, pharmacists generally negotiate with the health insurers on the prices of medicinal products, which negotiations may lead to the conclusion of a contract between pharmacist and health insurer. If a medicinal product is included in the contract between health insurer and pharmacist, the medicinal product is paid for by directly by the health insurer. Otherwise, a patient must pay themselves and may subsequently submit the bill to the health insurer for full or partial reimbursement. In addition to the costs of the medicinal product, pharmacists may charge patients for services offered, which may include control of the prescribed strength and dosage, control of interaction with other medicinal products, delivery, and explanation of how to administer the medicinal product.

15. What are the professional and legal responsibilities of those who dispense drugs and devices? What role do they play in providing patient care, information, and safety?

To protect safety and patient care, the prescription of medicinal products is reserved to a limited group of healthcare professionals. This group includes medical practitioners, dentists and to a limited extent other healthcare professionals, on the basis of Article 36(14) Individual Healthcare Professions Act (Wet Beroepen in de Individuele Gezondheidszorg) (“BIG Act“). Healthcare professions based in the Netherlands, including practitioners and pharmacists, must register in the Register for Individual Healthcare Professions (Beroepen in de Individuele Gezondheidszorg register) and are subject to disciplinary rules (Article 3 and 4(2) BIG Act). Pharmacists must comply with many specific professional guidelines that are set out by the Dutch Royal Pharmacists Association (“KNMP“), such as the KNMP Guidelines on the Legal Framework for Professional Standards for Pharmaceutical Care. In particular, pharmacists must also abide by the ‘principle of good care’ as laid down in Article 40 BIG Act. The principle of good care is an open, ethical norm which is further elaborated upon in the KNMP Guidelines. These guidelines are used by the relevant authorities to check compliance with the norm. In effect, the principle of good care means that a pharmacist must, in general, personally dispense a medicinal product directly to the patient. Prescriptions from healthcare professionals established in other Member States must in principle be recognized by Dutch pharmacists on the basis of the Dutch implementation of Directive 2011/24/EU on cross-border healthcare (i.e. Article 6.14 Medicines Act Regulation), provided that the ‘principle of good care’ does not oppose such recognition.

Cooperation between practitioners and pharmacists is in principle prohibited in the Netherlands to the extent that such cooperation is not in the interest of the ‘good provision of medicinal product’ (Article 11 Medicines Act Decree). The Dutch Supreme Court has ruled in that regard that it is not in the interest of the good provision of medicinal product for general practitioners to set up a pharmacy if that leads to a conflict of interest. In the case in question, 75% of the general practitioners in a town were shareholders of the local pharmacy, and thus had a considerable interest in the turnover and profit of the local pharmacy.

Foreign prescriptions must be accepted by Dutch pharmacies if they contain the information as mentioned by the Annex of the Commission Implementing Directive 2012/52/EU (Article 6.14(2) Medicines Act Regulation). Moreover, prescriptions from healthcare professionals established in other EU Member States must in principle be recognized by Dutch pharmacists on the basis of the Dutch implementation of the Cross-Border Healthcare Directive (i.e. Article 6.14 Medicines Act Regulation), provided that the ‘principle of good care’ does not oppose such recognition. Online prescriptions are prohibited if the prescriber has never personally met the patient (Article 67 Medicines Act).

Also from this Legal Handbook

2. Preclinical and Clinical Trial Requirements: The Netherlands

1. Are clinical trials required to be conducted locally as a condition (stated or implicit) for marketing approval?

No, clinical trials do not have to be conducted locally as a condition for marketing approval. This is not one of the prerequisite conditions for approval of the clinical trial protocol, which conditions are listed in Article 3 MRA. Clinical trials may be carried out at different locations. The MRA only requires the clinical trial protocol to show that the clinical trial is carried out in appropriate institution(s).

2. How are clinical trials funded?

The entity responsible for the funding of the clinical trial, referred to as the sponsor, can be another entity than the investigator itself. Clinical trials may be funded privately (e.g. by a biopharmaceutical company), publicly (e.g. by a hospital or university) or by a combination of both. The sponsor plays a central role in the management of the clinical trial, which includes the application for authorization under the CTR (Article 5 CTR).

The CTR defines the sponsor as the individual, company, institution or organization responsible for the initiation, for the management and for setting up the financing of the clinical trial.

The MRA defines the sponsor as a person, company, institution or organization which provides for the research, which entails the assumption of the responsibility for the initiation, organization and/or funding of the research (Article 1(1)(f) MRA). The investigator remains responsible for the conduct of the clinical research at the clinical trial site.

3. What are the requirements for pre-clinical and clinical trial protocols? Who must approve the protocols?

CTR

For the Netherlands, the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (“CCMO“) is the entity responsible for the review of preclinical and clinical trial protocols. The review is carried out by either the CCMO itself or by a Medical Research Ethics Committee (“MREC“) that has been accredited by the CCMO.

Research protocols that concern a new clinical trial within the meaning of the CTR (Article 2(2)) must be included in the application file which must be submitted via CTIS (see further Chapter 1, Question 3). Review takes place in accordance with the CTR. The Clinical trial protocols falling within the scope of the CTR must contain at least the information included in Annex I part D of the CTR.

MRA

Research protocols for research to which the CTR does not apply, but which fall within the scope of the MRA, must meet the requirements of and contain the information stipulated by Article 3 MRA. Research protocols are reviewed in advance by the reviewing committee (Article 2 MRA). The research may not be carried out unless the reviewing committee has issued a positive opinion.

The MRA applies if the following two conditions are met:

- the protocol concerns medical scientific research, excluding drug research falling under the CTR; and

- the research involves the imposition of actions or rules of conduct on persons which affect those persons’ physical and/or psychological integrity.

4. What are the requirements for consent by participants in clinical trials?

CTR

Informed consent is one of the core prerequisites for the enrolment of any person in a clinical trial under the CTR. A person, or where the person is not able to give informed consent, their legally designated representative, must be informed in accordance with the requirements of Article 29(2) to 29(6) CTR. This entails that:

- the person, or their legally designated representative, must be given information enabling the understanding of:

- the nature, objectives, benefits, implications, risks and inconveniences of the clinical trial;

- rights and guarantees regarding their protection, in particular the right to refuse to participate and the right to withdraw from the clinical trial at any time;

- the conditions under which the clinical trial is to be conducted, including the expected duration of participation; and

- the possible treatment alternatives (including follow-up measures if participation is discontinued);

- the information must be understandable to a layperson;

- the information must be provided in a prior interview and must also be prepared in writing, which is available to the subject (or their legally designated representative). During the interview, it must be verified that the subject has understood the information;

- information must be included on indemnification of any harm which may result from the clinical trial (see further Question 6 of this Chapter); and

- the subject must be informed that a summary of the results of the clinical trial and a summary presented in terms understandable to a layperson will be made available in CTIS.

MRA

Likewise, medical research which falls within the scope of the MRA is prohibited without prior written consent, which is to be provided in accordance with Article 6 MRA. Consent must be given in the following manner:

- if the participant has not yet reached the age of twelve, written consent of the legal parent or guardian is required.

- for participants aged between twelve and sixteen, both the participant and the legal parent or guardian must give written consent.

- participants who have reached the age of sixteen must give their consent in writing (this can be done electronically).

- if the participant is twelve years and older and is not capable of a reasonable appreciation of their interests, the legal parent or guardian must give consent.

- in the case of a participant aged sixteen who is not capable of a reasonable appreciation of their interests, the participant’s legal representative must give consent. In the absence of a legal representative, the spouse, registered partner or other life companion of this individual may also give consent.

Before consent is sought, the person must be informed of the following:

- the purpose, nature and duration of the research;

- the health risks associated with participation in the research;

- the risks interim termination would entail for the health of the subject of the research;

- the drawbacks which the research might entail for the person; and

- the manner in which consent may be given.

The information must be provided in such a way that it is reasonably certain that the participant has understood its contents and must be provided in writing at the request of the participant and/or in an interview prior to consent.

5. May participants in clinical trials be compensated?

CTR

The main rule under the CTR is that no undue influence, including that of a financial nature, may be exerted on persons for their participation in the clinical trial. For the categories of incapacitated participants, minors and pregnant women, the CTR prescribes that no incentives or financial inducements be given to the subject or their legally designated representative, except for compensation for expenses and loss of earnings directly related to participation in the clinical trial.

MRA

The MRA follows a similar approach. Participants may be compensated, subject to the following requirements:

- Compensation may not affect the giving of consent to participate in the clinical trial if the subject is under eighteen years of age (Article 3(1)(g) MRA);

- Compensation may not disproportionately affect the giving of consent to participate in the clinical trial if the subject has reached the age of eighteen (Article 3(1)(h) MRA);

- Compensation may not exceed an amount reasonably related to the nature, scope and purpose of the scientific research.

6. How are participants in clinical trials protected and indemnified against any harm that arises as a result of participation in the trial?

The CTR prescribes that Member States must implement a scheme providing for compensation for damage caused by participation in clinical trials within their territory (Article 76 CTR). The Netherlands has opted for compulsory insurance coverage for the conduct of clinical trials to ensure compensation for damage caused by participation in clinical trials. It is compulsory for the person/entity conducting clinical trials in the Netherlands to take out insurance prior to conducting the research (Articles 7 and 8 MRA). Specific requirements for the mandatory taking out of insurance for the conduct of clinical trials in the territory of the Netherlands are set out in the Medical Research (Human Subjects) Compulsory Insurance Decree 2015 (Besluit verplichte verzekering bij medisch-wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen 2015). The minimum requirements for the taking out, coverage and amount of the compulsory insurance set out in the Decree may not be derogated from to the detriment of the clinical trial participant (Article 8 of the Decree).

Also from this Legal Handbook

3. Marketing, Manufacturing, Packaging & Labeling, Advertising: The Netherlands

1. What is the authorization process for the marketing of new drugs, biologics, medical devices, non-prescription medications, and other medicinal products?

Please refer to Chapter 1, Question 3.

2. What is the authorization process for the marketing of generic versions of these products?

Please refer to Chapter 1, Question 6.

3. What are the typical fees for marketing approval?

Please refer to Chapter 1, Question 4.

4. What is the period of authorization and the renewal process?

Please refer to Chapter 1, Question 5.

5. What are the requirements, if any, for post-approval pharmacovigilance?

Please refer to Chapter 1, Question 8.

6. Are foreign marketing authorizations recognized?

Medicinal products

MAs granted by the MEB or by the EMA are recognized in the Netherlands. MAs granted by the regulatory authorities in other EU Member States can be recognized through the procedure of mutual recognition (see further Chapter 1, Question 3). MAs from non-EU states are not recognized in the Netherlands.

Medical devices

A manufacturer situated outside the EU has to appoint a sole authorized representative within the EU to be able to put medical devices on the market in the EU. Furthermore, only Notified Bodies within the EU are allowed to perform conformity assessment tasks and grant certificates. A conformity assessment from a Notified Body in one Member State grants the right to trade the medical device throughout the whole EU. An MA from a non-EU authority, such as the FDA, does not release a manufacturer from the obligation to obtain a conformity certificate from an EU Notified Body. However, the evaluating Notified Body can take the findings from the non-EU authority into account in its conformity assessment.

7. Are parallel imports of medicines or devices allowed?

Medicinal products

The parallel import of a medicinal product from another EU Member State or an EEA state into the Netherlands is permitted with a parallel trade authorization from the MEB. The medicinal product should be equivalent to a medicinal product that is already authorized in the Netherlands, including in terms of its pharmaceutical form and preferably also its package size. If the MEB already possesses the required information regarding safety as a result of the first marketing of a medicinal product in the Netherlands on the basis of an MA granted by the MEB, the MEB can grant an MA for the parallel-imported medicinal product according to a relatively simplified procedure (Article 48 Medicines Act).

Medical devices

The parallel import of a medical device from a non-EU Member State into the Netherlands is only permitted if the product is accompanied by a valid EU CE marking and DoC.

8. What are the restrictions on marketing practices such as gifts, sponsorships, consultancy agreements, travel and entertainment, or other incentives for healthcare organizations and individual medical practitioners?

Under Dutch law, inducement (gunstbetoon) is defined as the promise, offering or granting of money or services or goods that can be valued in money with the apparent aim of promoting the prescription, supply or use of a medicinal product or medical device (Article 1(1)(zz) Medicines Act and Article 6(1) Medical Devices Act). The inducement rules apply to all health professions and other persons who or organizations that professionally influence the choice regarding the medicinal product or medical device. This is a wide scope, which not only includes practitioners but also other persons with professional influence on the decision to use a particular medical device, e.g. a nurse or a purchaser at a healthcare institution.

In principle, inducement is prohibited for both medicinal products and medical devices. However, not all forms of inducement are prohibited. For both medicinal products and medical devices, the following exceptions apply (Article 94 Medicines Act and Article 6 Medical Devices Act):

- Providing compensation for the costs of participation in an event or not charging for participation in an event is permitted. However, such compensation must not exceed the amount that is strictly necessary to participate in the event.

- Remuneration for services rendered by healthcare professionals is permitted, provided the amount is reasonable and proportionate. In addition, the services provided must be relevant to the medical device supplier or healthcare professional involved.

- Gifts of a limited value (i.e. less than EUR 50, with a maximum of three gifts per individual healthcare professional per year) are permitted if they are relevant to the healthcare professional’s practice.

- Reduced rates and bonuses relating to the purchase of medical devices are permitted.

The rules on inducement for medicinal products and medicinal devices are explained in more detail in, respectively, the Policy Rules for Inducements under the Medicines Act 2018 and the Policy Rules for Inducements under the Medical Devices Act. These policy rules elaborate on the content and scope of the ‘inducement’, including in particular the exceptions to the prohibition of inducement listed above. The Inspectorate applies these policy rules in the enforcement of, respectively, the provisions on advertising of the Medicines Act and Article 6 of the Medical Devices Act.

Moreover, businesses are obliged to provide data regarding the financial relationship between healthcare professionals and businesses, along with the individual registration number, the BIG number of the healthcare professional, in a public transparency register (Article 13a of the Medicines Act Decree). Whether a relationship between a professional and a business qualifies as such is laid down in the Code to prevent undue influence through conflicts of interest (Code ter voorkoming van oneigenlijke beïnvloeding door belangenverstrengeling).

9. How is the manufacturing of medicines and devices regulated and by which agencies?

Manufacturers must adhere to the GMPs. The Inspectorate is responsible for the monitoring of the GMP standards and conducts inspections of compliance by manufacturers and wholesale distributors.

Medicinal products

The manufacturing of medicinal products and the wholesale distribution of medicinal products in the Netherlands is subject to a manufacturing or wholesale distribution authorization. The application for either type of authorization must be submitted to Farmatec. If the authorization is granted, Farmatec will register the authorization in EudraGMDP, the relevant EMA database.

Medical devices

Manufacturers of medical devices should manufacture the medical device taking into account the requirements for the CE marking.

See further Chapter 1, Question 3.

10. Are local manufacturing requirements compatible with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) as defined by the U.S. Food & Drug Administration and/or the European Medicines Agency?

Yes. The Netherlands has transposed the EU Directives on good manufacturing practices for medicinal products into Dutch law.

11. What is the inspection regime for manufacturing facilities?

The Inspectorate conducts periodic inspections of all manufacturers of medicinal products in the Netherlands, assessing whether the manufacturers comply with GMP and GDP. The Inspectorate usually combines the GMP and GDP inspections.

12. Are manufacturing facilities open for inspection by foreign inspectors or third-party inspectors as authorized by the FDA/EMA?

In principle, the Inspectorate conducts inspections at manufacturing facilities, if necessary in cooperation with the police, customs or the Fiscal Information and Investigation Service (the Fiscale inlichtingen- en opsporingsdienst (FIOD)).

The EU has signed a mutual recognition agreement with the United States that allows the FDA and the EMA to rely on each other’s inspections for products covered, in particular concerning human medicinal products.

13. What are the requirements for storage, packaging, and handling of medicines and devices and their constituent components?

Medicinal products

Storage and handling

The storage of medicinal products requires a wholesale permit (see also Chapter 1, Question 3). The wholesale permit is issued by Farmatec and is also required for the following activities: to have in stock, offer for sale, deliver or export or otherwise bring into or take out of Dutch territory, or operate a wholesale business in medicinal products for which an MA is granted (Article 38 of the Medicines Act).

The rules for storage and distribution are described in the EU Guidelines of 5 November 2013 on Good Distribution Practices (GDP) which give guidance on the obligation for wholesale distributors to appoint a responsible person with responsibility for implementation of and compliance with the GDPs, and on temperature conditions and monitoring, the training of personnel, documentation, the cleaning regime, and the storage of medicinal products or active substances.

To ensure sufficient availability of medicinal products, MA holders and wholesale distributors are obliged to hold sufficient stock of each medicinal product that they hold an authorization for or supply. This requires MA holders to ensure that the medicinal product covered by the MA is sufficiently stocked by wholesalers or pharmacists to meet patients’ needs (Article 49(9) Medicines Act). A wholesale distributor is obliged to hold such an assortment and stock of medicinal products that it can promptly meet the demand for a medicinal product. To further combat medicinal product shortages, as of 1 January 2023, MA holders and wholesale distributors are obliged to keep a ‘base stock’ (‘ijzeren vooraad’) of medicinal products. This base stock is a further interpretation of the obligation to hold sufficient stock and requires the MA holder to hold a stock of at least six weeks. The wholesale distributor should hold at least a two-week stock. This obligation will be extended to a stock of four weeks from 1 July 2023.

Packaging and labeling

The packaging and labeling requirements for medicinal products are set out by the MEB in the policy document MEB 6: Labelling of pharmaceutical products’ (“MEB 6“) and the EU Guideline on the Readability of the Labelling and Package Leaflet for Medicinal Products for Human Use (“Labeling Guideline“).

The information on the packaging must be clearly legible and non-erasable. The information must be presented in (at least) the Dutch language. An exemption from having to use the Dutch language may be granted in exceptional cases laid down in Article 4a.3(2) and (3) Medicines Act Regulation, in which case English is the only permitted alternative language. The product name must also be stated in braille.

The MEB 6 and Labeling Guideline define the items that must be included on the label, including:

- the name of the medicinal product;

- the active ingredient and excipients;

- the dosage strength of the medicinal product;

- pharmaceutical form and contents;

- any special warnings;

- expiration information;

- instructions for use;

- MA holder information; and

- Batch number and Unique Device Identification number (UDI).

For non-prescription medicinal products, the packaging should state the therapeutic indications and the instances in which the medicinal product cannot be used. Based on the rules laid down in the EU Falsified Medicines Directive (2011/62/EU), the packaging of prescription medicinal products should include a unique identifier code and an anti-tampering device, for example a seal on the packaging showing that the package has not been opened.

For more detailed packaging and labeling requirements we refer to policy document MEB 6 and the Labeling Guideline.

Medical devices

The requirements for medical devices are laid down in Annex I of the MDR and IVDR. The information on the packaging must be clearly legible and non-erasable and must include clear instructions for use that are adapted to the level of training and knowledge of the user. Instructions are only not required for class I or IIa medical devices or in some instances for in vitro diagnostic devices, and in the event that the device can be used safely without instructions for use.

The label with the information has to be placed on the device itself. If this is not possible, the information should be placed on the packaging of the device.

The information on the label must be in the Dutch language. However, for medical devices which are exclusively supplied to professional users, the information on the label and instructions for use can be in the English language.

The labeling requirements for medical devices include:

- the name of the medical device;

- necessary details for a user to identify the medical device, the contents of the packaging, and the intended purpose of the medical device;

- the name and address of the manufacturer or authorized representative;

- the lot number or the serial number of the device and Unique Device Identification number (UDI);

- an indication of the date by which the medical device should be used;

- any storage or handling instructions; and

- any warnings or precautions.

For certain medical devices, additional labeling requirements apply. All information and labeling requirements are specified in Annex I of the MDR (Article 23.1 of Chapter III and 23.2) and the IVDR (Article 20.1 and 20.2 of Chapter III). We refer to these articles for more detailed packaging and labeling requirements.

14. What information must be included in medicine and device labeling?

Please refer to Question 13 of this Chapter.

15. What additional information may be included in labeling and packaging?

Medicinal products

The use of signs, images or pictograms, as well as other information which corresponds to the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) by the EMA, which contributes to the health information for a user, is in principle permitted.

The MEB has compiled a list of symbols (listed in Annex 5 of the MEB 6) whose use is permitted. Images may only be used for clarification purposes and may not replace compulsory explanation in text. If signs, pictograms, logos or images are used, they should meet the following requirements:

- the image and text must be coherent;

- the use must correspond with the approved SmPC text and the text cannot be misleading;

- the use must be in line with the Labeling Guideline;

- the visuals must make the text more understandable;

- the use is not contradictory to good taste or decency; and

- the use does not contain any recommendation of the product and cannot be interpreted as any type of promotion of the medicinal product.

The packaging may not include direct or indirect references to (recommendations by) scientists or healthcare professionals.

Medical devices

According to Article 7 MDR, it is prohibited to use text or other signs in the labeling, instructions for use and advertising of devices that may mislead the user with regard to the device’s intended purpose, safety and performance.

16. What items may not be included in labeling and packaging?

Please refer to Question 15 of this Chapter.

17. What are the restrictions and requirements for the marketing and advertising of medicines and devices?

Medicinal products

Direct public advertising is prohibited for prescription-only medicinal products and for products that may be dispensed without a prescription that contain substances as referred to in list I or II of the Opium Act. Advertising for medicinal products without MA or a valid approval number issued by the Inspection Board for the Public Commendation of Medicinal Products (Keuringsraad Openlijke Aanprijzing Geneesmiddelen (KOAG)) is prohibited as well. Direct public advertising of other medicinal products is allowed, provided the relevant requirements are complied with.

The advertising rules for medicinal products are compiled in the Code of Conduct for Pharmaceutical Advertising which elaborates upon the relevant regulations of the Medicines Act and the Dutch Advertising Code (Nederlandse Reclame Code). Of particular relevance is the Code for Advertising Medicinal Products to the General Public 2019, part of the Code of Conduct for Pharmaceutical Advertising (see also Question 1 of this Chapter).

Compliance with the rules for public advertising of medicinal products is monitored by the Inspectorate in cooperation with the Health Advertising Knowledge and Advice Board (Keuringsraad Kennis en Advies Gezondheidsreclame).

Public advertising for any medicinal product must at least contain (Article 8.1 Code for Advertising Medicinal Products to the General Public 2019 (Code Publieksreclame voor Geneesmiddelen (CPG) 2019)):

- the name of the medicinal product;

- the generic name of the active ingredient (if the medicinal product contains only one active ingredient). This requirement does not apply for radio advertisements;

- the indications and contra-indications; and

- an explicit request to read the package leaflet or the text on the outer packaging. In media with space or time constraints, the statement ”please read the information on the package before buying” is considered sufficient, provided the outer packaging of the product contains full instructions for use, or an exhortation to read the package leaflet before use, provided that the statement does not mislead the consumer.

We refer to the Code of Conduct for Pharmaceutical Advertising for more detailed advertising requirements for prescription and non-prescription medicinal products (Articles 5.2 to 5.8).

Medical Devices