Market Access & Health Technology Assesment: Spain

Market Access & Health Technology Assesment: Spain is a must-have asset for any company operating in Spain or looking to enter the market.

Prepared in association with Faus & Moliner Abogados, a leading Spanish law firm.

October 2023

1. Healthcare System and Funding: Spain

1. Please make a general introduction to the public health sector in your country and its organization

The National Health System (“NHS”) is based on the principles of universal coverage and solidarity. Art. 43 of the Spanish Constitution establishes the right to healthcare as one of the basic principles that must inspire action by all public administrations, and this has been interpreted to recognise universal access to healthcare. The NHS is mainly funded from taxes.

Spain has a decentralized political system, with a central government and 17 regions, so-called Autonomous Communities. This has a relevant impact on the organization of the NHS because many healthcare competences have been transferred to the Autonomous Communities.

The central government is responsible for establishing the bases and general coordination of healthcare throughout the state, as well as for establishing legislation on pharmaceutical products. The Interterritorial Council of the National Health System (“CISNS”), which comprises the national health minister and the 17 regional ministers of health of each Autonomous Community (except for the two Autonomous Cities of Ceuta and Melilla), is responsible for high-level coordination of actions across the regional health system.

The central government, through the Ministry of Health, is also responsible for approving pricing and reimbursement of medicinal products. However, since the public funds that may be used to finance such reimbursement come out the budget of the 17 Autonomous Communities, such Autonomous Communities participate in the committee of the Ministry of Health (Inter-Ministerial Commission of Prices of Medicinal Products) responsible for assessing applications for price and reimbursement of medicinal products.

Regional governments, for their part, have broad powers on health matters, including the provision of public healthcare services and related funding.

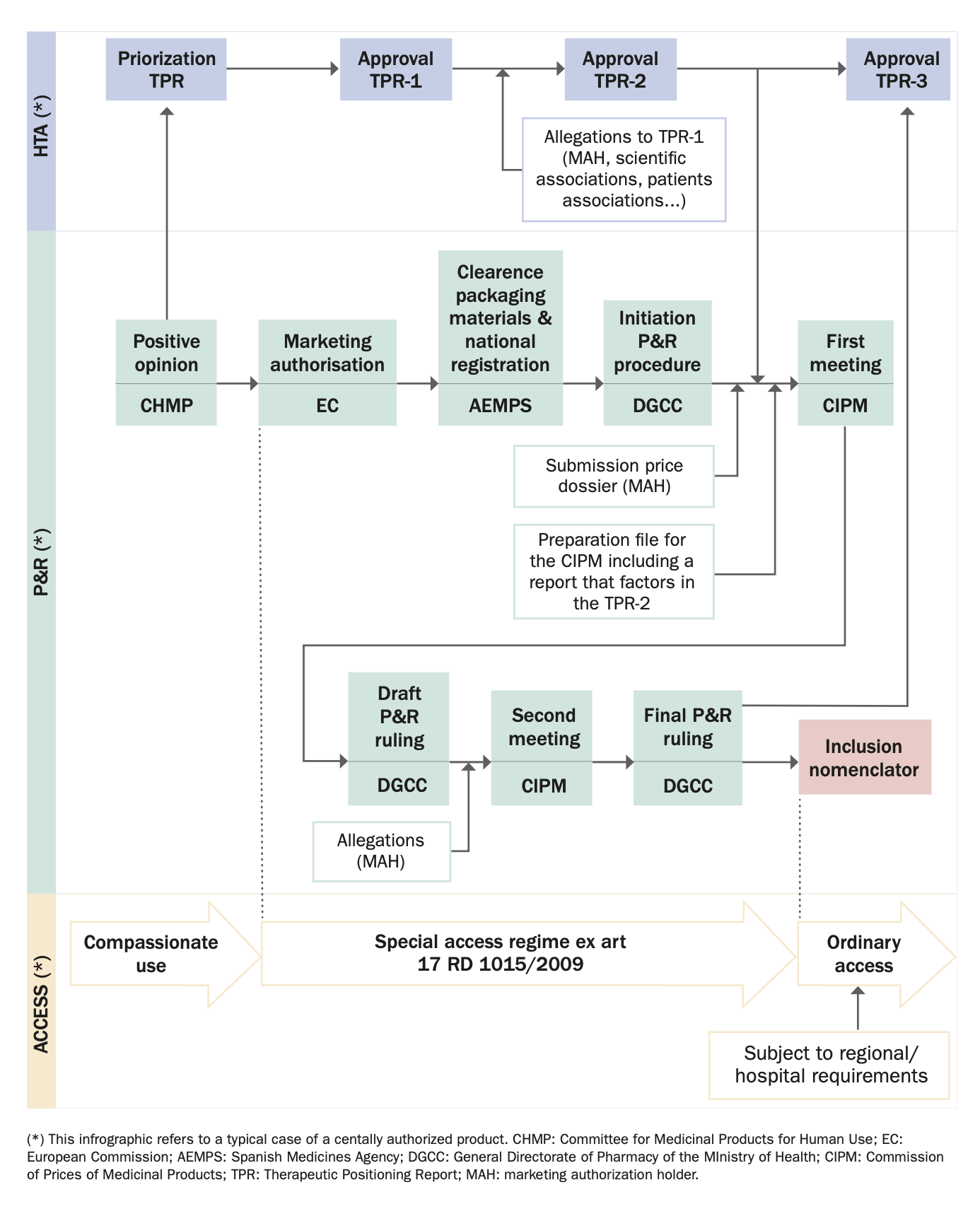

2. Please provide any infographics including, the actors involved in the market access process (market authorization, pricing decisions, reimbursement decisions); and the process and flow.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

2. Healthcare Actors and Payers: Spain

1. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of public health in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

The main administrations in charge of public health and reimbursement of medicinal products in Spain are: the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (“AEMPS”), the Ministry of Health (“MOH”), particularly the General Directorate of Pharmacy (“DGCC”), the Inter-Ministerial Commission of Prices of Medicinal Products (“CIPM”), the Advisory Committee for the Pharmaceutical Provision of the NHS, REVALMED (which is a net of different bodies in charge of HTA as we will discussed below)[1], and the health departments of the regional governments.

We will discuss the role of each of such bodies in the following questions.

2. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of drug approvals in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

The AEMPS is responsible for the evaluation and, where appropriate, authorization of medicinal products by national, decentralized (“DCP”) or mutual recognition procedures (“MRP”). Its legal regime and functions are contemplated in Royal Decree 1275/2011 which created the AEMPS and approved its Statute.

In addition, the AEMPS plays an important role in the process of preparing the Therapeutic Positioning Report (“TPR”) to which we will refer below.

3. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of Health Technology Assessment in your countries and what are their respective responsibilities?

There is some confusion in Spain on this issue; especially after the recent Judgement of 26 June 2023 by the Spanish National High Court that has annulled the Plan to consolidate TPRs that the MOH had approved to regulate the preparation of TPRs (the main HTA instrument in Spain for medicinal products). The European HTA Regulation also adds uncertainty to this scenario insofar as it is still unclear how the evaluation reports foreseen therein will affect Spanish TPRs.

Be it as it may, as things stand, the main bodies in charge of HTA in Spain are the AEMPS, the MOH and the regional governments; all of such bodies acting in coordination through REVALMED. This statement, however, needs to be qualified and contextualized. We do so below.

First, the main HTA instrument for medicinal products in Spain is the TPR. TPRs were created in 2013 with the objective “to provide, beyond the authorization of the medicinal product, relevant information, based on scientific evidence of the position that the new product occupies in the market in comparison with other drugs or health measures already in existence”[2]. The legal basis for such TPRs is Third Additional Provision of Law 10/2013 which establishes that the position of a medicinal product in the pharmaceutical provision and its comparison with other therapeutic alternatives will be carried out through TPRs, which are binding, and have to be elaborated and approved by the AEMPS, having a common scientific-technical basis for the entire NHS.

Second, notwithstanding what is said in Law 10/2023, in 2020 it was approved the so called “Plan to Consolidate TPRs”, which created REVALMED[3], a network under which other agencies, in addition to the AEMPS, have a relevant role in the preparation and approval of the TPRs. REVALMED has been responsible for the coordination of the TPR process in Spain since 2020, and is composed of:

- Therapeutic Evaluation Group. Its function is to prepare the first draft of the TPR with regard to the therapeutic sections. It is led by the AEMPS, although it also includes members of the DGCC.

- Pharmaco-Economic Evaluation Group. Its function is to prepare the first draft of the TPR with regard to pharmacoeconomic aspects. It is led by the DGCC, although it can also include members appointed by the Autonomous Communities.

- Evaluation Nodes. Their function is to review the draft of the TPR and make contributions. They are made up of expert management and clinical professionals appointed by the Autonomous Communities.

- Coordinating Group. Its function is to identify the TPRs to be developed, prioritize them (according to certain pre-defined criteria) and, finally, approve them. It is made up of members of the DGCC, the AEMPS, coordinators of the Evaluation Nodes and representatives of the Autonomous Communities.

Third, since approval of the Plan to Consolidate TPRs in 2020, some TPRs also include pharmaco-economic evaluation assessments. This inclusion has created some tension and discrepancies among relevant stakeholders who question whether TPRs are the appropriate instrument for incorporating this type of evaluation.

Fourth, Farmaindustria (the National Trade Association of the Spanish based pharmaceutical industry) appealed the Plan to Consolidate TPRs. The legal basis of the appeal was based on two arguments. First, the Plan to Consolidate TPRs is in the nature of a general provision. It is not a mere internal organizational instrument, as the MOH defended. This being so, Farmaindustria requested the nullity of the Plan as it was approved by a manifestly incompetent body (the Committee on Pharmacy of the CISNS) with absolute omission of the legally established procedure. Second, the Plan to Consolidate TPRs must be annulled because it is contrary to the principle of hierarchy of norms. The Plan to Consolidate TPRs provides that TPRs will have a “scientific and economic basis”, and that they will be approved by the REVALMED Coordination Group. However, Law 10/2013, the only legal basis for the TPRs, provides that TPRs “shall have a scientific basis” (without any mention of the economic issue) and must be approved by the AEMPS.

The Spanish National High Court upheld the appeal in its entirety. The Judgement (as per the information available at the time of publication) was not appealed.

As stated above, the impact of this Judgement to the Spanish HTA process is still unclear but it is likely that it will imply profound changes in that process over the coming months. Close follow-up of the topic will be necessary.

4. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions that qualify as “payers” in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

Spain’s regional governments pay for all healthcare services from their own budgets. They enjoy a large degree of autonomy to decide how they purchase the goods and services they may require to provide healthcare services to patients.

The MOH is the department of the central government responsible for approving the reimbursement of medicinal products. As explained, the public funds that may be used to finance this reimbursement come out of the budgets of the 17 Autonomous Communities into which Spain is divided. Because of this, the Autonomous Communities participate in the CIPM, the specific committee within the MOH responsible for assessing applications and deciding on the maximum ex-factory price (so called “PVL”, which stands for “Precio Venta Laboratorio”) for reimbursed medicinal products.

This generates a complex situation where the basic content of the pharmaceutical provision is set forth at the state level (because the MOH makes the decision on pricing and reimbursement, as explained below) but regional governments are responsible for financing it out of their budgets.

5. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of reimbursement decisions in your countries and what are their respective responsibilities?

The MOH, particularly the DGCC, is the department of the central Spanish government in charge of pricing decisions of medicinal products. The DGCC’s functions are contemplated in Royal Decree 735/2020. Such functions include deciding on whether a medicinal product shall be reimbursed or not by the NHS and providing technical and administrative support to the CIPM.

The CIPM is a collegiate body formed by representatives of the MOH, the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation, the Ministry of Treasury and representatives of the Autonomous Communities. The CIPM is responsible for deciding on the maximum ex-factory price for reimbursed medicinal products (PVL). Its specific legal regime is contemplated in Law on Rationale Use of Medicines and Medical Devices (Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015) and in Law on Legal Regime of the Public Sector (Law 40/2015).

The MOH, through the DGCC, and the CIPM, decide on reimbursement and then on price. In theory, the DGCC is the first to decide whether the product is reimbursed, and the CIPM then decides on the maximum reimbursed price. In practice, however, the two procedures run in parallel and overlap because the decision of the DGCC regarding reimbursement is also based on the price that the CIPM would set for the product. The DGCC, on the other hand, takes care of process management, preparing the rulings that the CIPM shall adopt. It is also the de facto leader of the negotiations with the Marketing Authorization Holder (“MAH”) and coordinates the work carried out by evaluation groups who handle the dossiers prior to the meeting of the CIPM.

6. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of reimbursement decisions in your countries and what are their respective responsibilities?

See Q5 (Section II).

7. Which are the administrations, bodies and institutions in charge of public procurement and tendering in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

Regional governments and public hospitals are in charge of public procurement and tendering in Spain. See Section IX below.

8. What are the other actors of significance with regards to market access in your country and what are their respective responsibilities?

The Autonomous Communities play a large role in market access. This is because even though the MOH decides which therapies are financed, the Autonomous Communities allocate the budget for financing such therapies. This means that in the case of high budgetary-impact products, companies may expect access to the market to be subject to agreements with regional authorities (or sometimes with local hospitals) regarding the conditions under which the product will be available in such a region or hospital.

The role of the Autonomous Communities become even more relevant for non-reimbursed products, that is products that the MOH has decided not to reimburse. The purchase of such products by the Autonomous Communities is subject to the approval of the relevant Therapeutic Commission of each Autonomous Community. Such Commission may decide whether such non-reimbursed product may be purchased by hospitals of the Autonomous Community or not.

[1] REVALMED has been recently questioned by a Court Judgement as we indicate in different sections of this publication.

[2] Collaboration proposal for the elaboration of Therapeutic Positioning Reports of medicinal products, accessible at: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/informesPublicos/docs/propuesta-colaboracion-informes-posicionamiento-terapeutico.pdf.

[3] Plan to consolidate the Therapeutic Positioning Report in the National Health System, accessible here: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/docs/20200708.Plan_de_accion_para_la_consolidacion_de_los_IPT.actCPF8Julio.pdf.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

3. Post Market-Approval Processes and Regulations: Spain

1. What are the pricing models, processes and principles for originator drugs?

Originator medicinal products must go through price and reimbursement proceedings (P&R Procedure) where it is decided if they are to be reimbursed or not. If reimbursed, the PVL is also fixed.

To determine whether a medicinal product is reimbursed or not, the DGCC/CIPM must take into account the following criteria (art. 92 and 94 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015):

- the seriousness, duration and sequels of the pathologies for which the product is approved;

- the needs of special groups of people;

- the therapeutic and social utility of the product as well as its incremental clinical benefit, taking into account its cost and effectiveness;

- the need to limit and rationalise public pharmaceutical expenditure and the impact of the medicinal product on the NHS;

- the existence of medicines already available and the existence of other alternatives for the same illnesses, which have a lower price;

- budget impact and cost-effective analysis;

- The contribution of the product to Spain’s gross domestic product;

- the degree of innovation of the product: whether it provides an indisputable therapeutic advance for altering the course of an illness or easing the course of such illness; and its results or contribution to the NHS;

- The return mechanisms that may be proposed by the MAH (discounts, price reviews). This is the result of the increasing relevance that risk-sharing schemes are currently having in Spanish practice; many companies, especially for high-budgetary-impact products, are required to offer specific arrangements to obtain reimbursement.

From a procedural standpoint, the typical P&R Procedure (there may be particularities/changes on a case-by-case basis) incorporates the following phases: (i) initiation: the P&R Proceeding starts ex-officio; the DGCC shall send a letter to the MAH or to its local representative (“LR”), informing it that the process has begun and granting the MAH a period between 10 and 15 working days to make any submission it deems convenient on the reimbursement of the product, (ii) negotiation between the MAH/LR and the DGCC, and preparation by the DGCC of a report for the CIPM in which the DGCC performs a therapeutic (and sometimes economic) evaluation of the new drug/new indication (this report is commonly referred to as the “Associate Report for the CIPM” or “Associate Report”), (iii) evaluation of the new medicinal product/new indication by the CIPM, (iv) issuance by the DGCC of a draft resolution on the reimbursement/non reimbursement of the new medicinal product/new indication as resolved by the CIPM, (iv) submission of allegations by the MAH/LR (if any), (v) assessment of the allegations by the CIPM/DGCC (if any) and (vi) final ruling of the DGCC.

Under the law, the whole P&R Proceeding may take up to 180 days. However, authorities usually request additional information, and these requests may stop the clock on the procedure. In practice, companies may well expect the reimbursement approval to run for a minimum of six months. Occasionally, procedures have taken longer.

2. What are the pricing models, processes and principles for generics and biosimilars drugs?

Theoretically, generics and biosimilar drugs must go through the same P&R Procedure explained in Q1 (Section III) above. However, in practice, what usually happens is that such products go through a sort of “simplified” P&R Procedure which, in essence, means that generics/biosimilar products are reimbursed with an approximate 40% (generics) or 20-30% (biosimilars) discount with respect the originator.

3. What are the reimbursement approval processes and principles for originator drugs?

Please refer to Q1 (Section III) above.

4. What are the reimbursement approval processes and principles for generics and biosimilar drugs?

Please refer to Q2 (Section III) above.

5. Are there any other special processes to be considered for certain types of drugs?

Non-industrially manufactured advanced therapy medicinal products (“ATMPs”) are subject to a special P&R Procedure.

In October 2019, the CISNS issued an agreement on the general conditions for planning, coordination, contracting, procurement and supply of ATMPs for the publicly owned structures and services integrated in the NHS (the “2019 Agreement”).

In the 2019 Agreement, the CISNS confirmed that for the reimbursement of medicinal products, their inclusion in the pharmaceutical provision of the NHS is necessary because this is contemplated in art. 92.1 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015. However, in contrast to industrially manufactured medicinal products where the DGCC and CIPM are competent (see Q5 Section II), the 2019 Agreement determined that CISNS is the competent body to decide on the reimbursement of non-industrially manufactured ATMPs.

The 2019 Agreement was based on the opinion of the State Attorney who relied on art. 91.6 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 that expressly states that “[T]he Interterritorial Council of the National Health System may agree on the general conditions for planning, coordination, contracting, procurement and supply of medicines and medical devices of the publicly owned structures and services integrated in the National Health System”.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

4. Price Control and Reference Pricing Systems: Spain

1. Price Control

1. How does price control at ex-factory prices work in your country?

This question may be broken down in two parts: (i) situations in which a medicinal product may be in connection with its reimbursement status/price; and (ii) criteria to determine PVL.

Situations in which a medicinal product may be in connection with its reimbursement status/price:

- Medicinal products that have been granted a MA but for which a reimbursement/price ruling has not been issued.

They may be available in Spain ex art. 17 in fine of Royal Decree 1015/2009 regulating the availability of medicines in special situations. Their use must be authorized by the AEMPS, either for an individual patient or for a specific subpopulation of patients (protocol for use).

Their price is free (not regulated), and it is set by the supplier, usually after negotiation with the hospital pharmacy service. It is not uncommon for hospitals to pressure the company to supply the product free of charge, especially for those patients who were being treated with the medicinal product in the context of a clinical trial. The company has no legal obligation to supply the product free of charge except if the company obtains some information from the administration of the medicinal product (art. 31 and 39.1.f of Royal Decree 1090/2015).

- Medicinal products that have been granted a MA and for which a reimbursement/price ruling has already been issued.

Their commercialization is carried out at the following maximum prices.

For units dispensed in Spain at the expense of the NHS, the maximum reimbursement price is the PVL set by the CIPM.

For units dispensed outside the NHS (that is not reimbursed units), the maximum price at which they can be marketed is the “notified price”. The notified price is free although the DGCC can object to it for reasons of public interest ex art. 94.4 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015. Since there is no specific term for the DGCC to express this objection, we understand that the general term of 3 months applies.

- Medicinal products that have a MA and an express non-reimbursement ruling of the DGCC.

According to a Report issued by the DGCC in 2019, the managing entities of the NHS and/or public hospitals cannot acquire medicinal products in this situation. In our opinion, this conclusion of the Report has no legal support and, therefore, lacks any legal validity. Among other issues, the DGCC has no authority to issue such a report. Moreover, there is no regulation that prohibits public hospitals from acquiring these medicinal products; in fact, this possibility is specifically contemplated in Royal Decree 1718/2010 on medical prescriptions and dispensing orders. Be that as it may, the reality is that in practice some Autonomous Communities follow the criteria of the Report and do not purchase medicinal products with an express non-reimbursement ruling.

In our opinion, medicinal products with an express non-reimbursement ruling of the DGCC can be marketed outside the NHS at free price.

- Medicinal products that have a MA but have never been reimbursed and have never been the object of an express non-reimbursement ruling of the DGCC.

They can be marketed at free price.

- Medicinal products that had been reimbursed but have been subsequently excluded from reimbursement.

They can be marketed at free price. However, this price must be communicated to the MOH so that, within a period of one month, it can decide on its conformity (art. 93.3 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015). In case of disagreement, the file is submitted to the CIPM, which must decide on the basis of “reasons of protection of public health, equal access to medicines for patients or actual or potential harm to the interests of disadvantaged groups”. As long as the disagreement is maintained, the maximum industrial price that the product had when it was reimbursed remains in force (art. 93.5 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015).

- Non-prescription medicinal products.

They can be marketed at free price unless the Government regulates them “following a general objective and transparent regime” (art. 94.3 par 1 of the Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015) or unless the CIPM, when there is an exceptional health situation, and in order to protect public health, fixes the maximum retail price (“PVP”) for the duration of such exceptional situation (art. 94.3 par 2 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015).

PVL:

As discussed above, units of medicinal products for which a reimbursement/price ruling has already been issued by the DGCC and that are dispensed in Spain at the expense of the NHS [point (ii) above] cannot be commercialized at a price above the PVL set by the CIPM.

How is this PVL set?

As regards setting the price of medicinal products, Spain has always been said to follow a “cost plus” system, under which the maximum PVL should respond to the cost of the product plus a given profit margin. This is what Royal Decree 271/1990 contemplates in accordance with the provisions of Directive EC 89/105.

As a matter of practice, it has always been known that the price-approval process entails a negotiation with the authorities where the cost and the profit margin are not really the variables that are considered. Companies should be prepared for prices mainly to be determined by the following two issues: a) a comparative pharmaco-economic evaluation of the medicine in which the advantages of the new product should be quantified; or b) the price of the product in other EU Member States.

Other than these, companies must be ready for the authorities to consider other issues such as the activities performed by the company in Spain (R&D, manufacturing, etc.) and the relationship with a local company through a co-marketing or licensing arrangement.

2. How does price control at the wholesale level work in your country?

Please refer to the question above.

3. How does price control at the retail pharmacy level work in your country?

The margin of retail pharmacies (“Pharmacy Margin”) is regulated in art. 2 of Royal Decree 823/2008.

Pharmacy Margin is: (i) for those medicines whose PVL is equal to or less than €91.63, 27.9% of the retail price excluding taxes (“Retail Price”); (ii) for those medicines whose PVL is higher than € 91.63 and equal or lower than €200, €38.37 per package; (iii) for those medicines whose PVL is higher than €200 and equal or lower than €500, €43.37 per package; and (iv) for those medicinal products whose PVL is higher than €500, € 48.37 per package.

2. External Reference Pricing (ERP)

1. Is there a system of external reference pricing (ERP) in place in your country?

As per written Spanish law, the MOH is not allowed to reference prices internationally. International referencing was contemplated in the Law on Medicinal Products before 2012, but Royal Decree-Law 16/2012 of 20 of April revoked any reference to this practice in 2012 and from then on, international referencing has no legal basis in Spain. The Judgements of the Supreme Court of 28 October 2015 and 11 November 2015 confirmed this understanding.

With respect ERP, however, the theory substantially differs from the practice. While it is clear that the law does not allow the MOH to reference prices internationally, the truth is that ERP is, indeed, a quite relevant factor influencing price rulings in Spain (with respect both the PVL and the Notified Price). The fact that this practice has no legal basis, makes it quite difficult to identify how the MOH exactly factors in international prices and from which sources these prices are obtained. In any case, as per our experience dealing with the MOH, it has become clear that, on the one hand, the MOH requests the MAH to provide information about how the medicine has been priced in other EU countries; and, on the other hand, that EU prices operate as a cap for Spanish prices, meaning that prices in Spain are rarely fixed above the price of the same medicinal product in other EU countries.

2. When and/or how often is ERP activated?

Please refer to Q2.1 (Section IV) above.

3. What is the legal framework of the ERP in place in your country?

Please refer to Q2.1 (Section IV) above.

4. What is the composition of the country basket?

Please refer to Q2.1 (Section IV) above.

5. Describe the price calculation and selection for reference products.

Please refer to Q2.1 (Section IV) above.

6. How often does the price need to be updated?

Please refer to Q2.1 (Section IV) above.

7. How do the “price List”/catalogues from references countries work in your country?

Please refer to Q2.1 (Section IV) above.

3. Internal Reference Pricing (IRP) (Note, this is not applicable in some market, develop if is applicable to your country)

1. Is there an internal reference pricing (IRP) system in your country?

Yes. Once a generic or biosimilar version of a medicinal product is approved, or even if no generic or biosimilar exists in Spain but the main active ingredient of a product has been authorised in the EU for the last 10 years (and there exists at least one medicinal product different than the original product and its licences), the MOH may make such ATC5 substance subject to a reference price, which will apply to all reimbursed product presentations having the same ATC5 classification and identical administration route.

The reference price is the maximum price which the Spanish authorities will pay for these products. Such price is fixed on the value represented by the lowest cost of treatment per day of the presentations of the medicinal products included in each group.

2. What is the legal framework of the IRP in place in your country?

Spanish IPR is regulated in the Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 and in the Royal Decree 177/2014 on the reference price system.

3. When and/or how often is IRP activated?

The MOH approves a reference price list every year based on the information in the database for reimbursed and marketed products (Nomenclator) as of April 1st. The list published by the MOH is called Reference Price Order (“RPO”). A draft of the RPO (to which companies may submit allegations) is usually published in Q2-Q3 of each year. The final RPO is usually published in Q3-Q4 of each year.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

5. HTA Decision Analysis Framework: Spain

1. Which are the health technology assessment (HTA) evaluation bodies and their responsibilities in your country?

The main bodies in charge of HTA in Spain are the AEMPS, the MOH (particularly the DGCC) and the regional governments; all of such bodies acting in coordination through REVALMED.[1] Also note that, as mentioned above, a recent Court Judgment (26 June 2023) annulled the documents that served as the basis for REVALMED and that, therefore, it is foreseeable that there will be important changes in this matter (including key players and bodies in charge of HTA in Spain) in the near future. For further details, see Q3 Section II above.

2. Do regulators require HTA studies in your country?

Regulators do no requite HTA studies for the application/obtention of MAs of medicinal products in Spain. To obtain a MA in Spain (following a national authorization procedure), medicinal products developers need to submit specific data on their medicinal product (dossier) that does not include HTA reports nor other type of studies comparing the assessed medicine with other medicinal products/therapies. The AEMPS then carries out a thorough assessment of such dossier to decide whether or not the particular medicinal product is safe, effective and of good quality and is therefore suitable for use in patients.

3. Do payers require HTA studies in your country?

Generally speaking, yes. Although it depends on the specific medicinal product or new indication assessed for P&R purposes.

According to Law 10/2013, TPRs have been interpreted as compulsory for pricing decisions, although the wording of Law 10/2013 is not entirely clear and may be interpreted otherwise.

The Plan to Consolidate TPRs (recently annulled by a the Spanish National High Court, as discussed above) also seemed to indicate that TPRs are compulsory for P&R purposes in the following cases: medicinal products and new indications authorized by the European Commission through a centralized procedure, new medicinal products authorized through a national procedure that contain new molecules, and all other medicinal products that the Permanent Commission of Pharmacy so considers considering its budget and sanitary impact.

In practice (and until now, this may change in the future due to the profound changes that the Judgment annulling the Plan to Consolidate TPRs may bring), TPRs have been mandatory for P&R Procedures in the cases outlined above. The DGCC (saved from very rare occasions) does not elevate a P&R dossier of new medicinal products/new indications to the CIPM until the TPR is ready and available.

4. How are HTA assessments translated into pricing conditions in your country?

In accordance with Royal Decree 271/1990 (still in force and fully applicable), Spanish authorities should follow a “cost plus” system under which the maximum PVL should respond to the cost of the product plus a given profit margin. Therefore, at least theoretically under Spanish written laws, HTA assessment should have no impact into pricing conditions.

However, as already discussed, the reality is different, and comparative pharmaco-economic assessments are often used to determine pricing conditions. In this respect, whenever a TPR has been approved, it heavily influences reimbursement and pricing decisions. How exactly the results of the TPR are factored in a pricing decision is hard to say, to the extent there is no legally mandatory guidance to be followed in this respect. In Spain, there are not mandatory cost-effectiveness thresholds either (although GENESIS’s guidelines[2] include some non-binding references). Be it is at may, we think is fair to say that whenever a TPR has been approved it is well taken into account by the authorities in charge of pricing decisions (DGCC/CIPM).

Finally, it is also relevant to note that Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 (arts. 92.1.c and 92.8) contemplates that cost-effectiveness assessments may affect reimbursement decisions. Strictly, Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 refers to “reimbursement” decisions (i.e., whether to reimburse or not) but not pricing ones (fixing the maximum ex-factory price in case a given product is reimbursed). Anyway, this reference, the fact that the reimbursement decision and the pricing decision overlap to certain extent (because the decision of the DGCC regarding reimbursement is also based on the price that the CIPM would set for the product), and the usual practice described in the preceding paragraph, allow us to conclude that HTA assessments have, indeed, a relevant impact in pricing conditions.

5. How are HTA assessments translated into reimbursement conditions in your country?

Please refer to Q4 (Section V) above.

6. Which are the evaluation criteria, processes or models and analyses framework used for HTA in your country?

There are no ex lege mandatory criteria, processes or models that must be followed in Spain to perform HTA assessments. Anyway, it is worth noting the existence of a standard operating procedure (SOP) to perform TPRs[3] approved by the Permanent Commission on Pharmacy of the CISNS and some guidelines developed by the GENESIS group[4]. Such documents, although not binding, have had a relevant impact on criteria, processes and models used in HTA assessments during the last years. The SOP, in any case, derives from the Plan to Consolidate TPRs which, as indicated above, has been declared null and void. This means that the legal validity of the SOP could also be questioned.

7. What is the methodology used in your country for HTA assessment?

There is no ex lege mandatory methodology that must be used in Spain for HTA assessments. The guidelines mentioned in the prior question (SOP to perform TPR[5] and GENESIS’s guidelines[6]) have also had some impact on the methodology used in Spanish HTA assessments over the last years.

8. Which are the other decisions impacted by the assessed outcome in your country?

The objective of the Spanish HTA assessments (included in the TPRs) is to provide a comparative therapeutic and economic evaluation of medicinal products in order to have relevant information, based on scientific evidence, on the position of the new product or its new indication compared to existing therapeutic alternatives, pharmacological or otherwise.

Such HTA assessments have an impact in several areas (apart from P&R decisions) including the selection, prescription and use of medicinal products. The Autonomous Communities and hospitals may also perform local HTA assessments, and such assessments may sometimes be influenced by the content of the TPRs (nationwide HTA assessment).

9. Does your HTA review or inquire other international HTAs during the assessment process? If so, which ones are the usual partners?

There is no list of international HTAs assessments that Spanish authorities must review before carrying out its own assessment. The SOP to perform TPR[7] and GENESIS’s guidelines[8] include some instructions on how to consider and assess the results of international evaluations, but do not refer to any specific international HTAs for that purpose.

Finally, it is relevant to mention that the DGCC almost always includes a section called “conclusions of other evaluation bodies” in the Associate Report for the CIPM (this is a report that includes the results of the TPR, some other therapeutic and economic evaluations, and a recommendation to the CIPM on whether or not to reimburse the medicinal product). In this section it is common to see references to evaluations made by NICE or French HTA evaluation bodies.

[1] As discussed, REVALMED has been recently questioned by a Court Judgement.

[2] Accessible at: https://gruposdetrabajo.sefh.es/genesis/genesis/Documents/GUIA_EE_IP_GENESIS-SEFH_19_01_2017.pdf

[3] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[4] Accessible at: https://gruposdetrabajo.sefh.es/genesis/genesis/Documents/GUIA_EE_IP_GENESIS-SEFH_19_01_2017.pdf

[5] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[6] Accessible at: https://gruposdetrabajo.sefh.es/genesis/genesis/Documents/GUIA_EE_IP_GENESIS-SEFH_19_01_2017.pdf

[7] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[8] Accessible at: https://gruposdetrabajo.sefh.es/genesis/genesis/Documents/GUIA_EE_IP_GENESIS-SEFH_19_01_2017.pdf

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

6. HTA Dossiers: Spain

Before answering the questions in this Section VI, it is appropriate to make an important consideration. In Spain, at least up to the date of this publication, the HTA evaluation is carried out by public authorities, without the industry having to provide a specific HTA dossier with pharmacoeconomic studies of its product.

Once the process has started (which we will detail in the following questions), the company that owns the product (and other relevant stakeholders) have the right to present “allegations” to the TPR draft. And at this point, they can provide studies to support their position. But there is no HTA dossier submission at the very beginning of the HTA process.

The Advisory Board of the NHS (“CAPF”) has issued several reports in favour of changing the current model and increasing the role of the industry in the HTA process (always preserving, the public authorities right to review the work done by the industry and to perform its own HTA assessments)[1].

1. Have local authorities published recommendations surrounding value assessment dossiers? (If yes please add link)

The most relevant non-binding recommendations for performing pharmacoeconomic evaluation and budget impact analysis are the GENESIS’s guidelines[2] mentioned in the prior Section. The SOP for TPRs[3], and a Q&A prepared by the MOH[4] may also be useful for such purposes.

2. Have local Authorities published guidelines surrounding value assessment dossiers? (If yes please add link)

The most relevant non-binding guidelines for performing pharmacoeconomic evaluation and budget impact analysis are the GENESIS’s guidelines[5] mentioned in the prior Section. The SOP for TPRs[6], and a Q&A prepared by the MOH[7] may also be useful for such purposes.

3. Have local authorities published official guidelines surrounding the submission of value assessment dossiers? (If yes please add a link)

Two considerations shall be made prior to answering this question. First, as discussed in the beginning of this Section, there is no formal HTA dossier submission in Spain. Second, as pointed out in Question 3 (Section II), the main document governing HTA in Spain (i.e., the Plan to Consolidate TPRs) have been annulled by the Spanish National High Court. This means that, as of today, there is a lot of uncertainty as to how HTA assessments will be done in the future.

Be it as it may, until the date of publication of this guide, the main steps of the HTA process in Spain were as follows:

- Positive opinion of the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP).

- The Coordination Group of REVALMED establishes a priority order of the medicinal products with a positive CHMP opinion. The prioritization criteria include, among others, covering an unmet therapeutic need or having a better clinical benefit or safety profile with respect to therapeutic alternatives.

- First draft of the TPR. The different groups (including the Therapeutic and the Pharmacoeconomic groups and the Evaluation Nodes) (see Question 3, Section II) prepare the first draft of the TPR. This first draft is approved by the Coordinating Group.

- Allegations of relevant stakeholders (including scientific societies, patients’ associations and the MAH) to the first draft of the TPR.

- Review of the allegations by the relevant groups and approval of the so-called Phase II TPR which may or may not include the proposals of the relevant stakeholders. The Phase II TPR is disclosed and published at the AEMPS’ website. The Phase II TPR is the one that is used for the DGCC to prepare the Associated Report for the CIPM. It is, therefore, the HTA report that has an impact on P&R decisions.

- After the P&R ruling, the TPR should be adapted including the price of the medicinal product. This is the Phase III TPR.

4. Describe the overall process of preparing and submitting a HTA dossier in your country.

As discussed, the nationwide HTA assessment for medicinal products in Spain is included in the TPR. Until the date of publication of this guide, TPRs include all or part of the following content:

- The title of the TPR shall include the name of the medicinal product and the clinical indication evaluated.

- The introduction shall clearly and precisely state the indication for which the product has been authorized and shall contain two parts: description of the health problem and current treatment. The introduction section also includes information about the following very relevant aspects: patient groups that may benefit the most from the treatment, comparators, treatment objective, relevant clinical variables as well as the threshold of clinical relevance in those cases in which a commonly accepted threshold is available.

- Description of the medicinal product. It should include the name of the active ingredient (trade name) and a brief introduction of the new product (therapeutic indication, presentation, dosage and pharmaceutical forms). It may also include aspects of the administration or duration of the treatment and relevant aspects of the authorization (for example, if it is a new medicinal product or a new indication, if the medicinal product has been designated orphan, if it has conditional or exceptional authorization, if it is conditioned to the results of new studies, etc.).

- Data from studies, including pivotal studies with active comparator, mainly the reference standard in clinical practice, and variables suitable for positioning the product will be prioritized for establishing the therapeutic position of the medicinal product.

- This section should follow a similar approach than the “Efficacy” section.

- Clinical benefit assessment and relevance for clinical practice. The objective is to assess whether the magnitude of the treatment effect is of clinical relevance, whether equivalent therapeutic alternatives exist, etc.

- Economic evaluation. The inclusion of this section in the TPRs has been questioned by the Spanish National High Court Judgment. Please refer to Q3 Section II for further information.

- The discussion section should lay the foundations for the conclusion of the report, establishing the argumentative thread that leads to the positioning of the medicinal product.

- Based on the discussion section, this section should establish the contribution of the product for the entire indication or for different subpopulations of the indication. The objective is to position the product as precisely as possible, based on the criteria of efficacy, safety and efficiency and its comparison with available alternatives.

- Therapeutic positioning. This is established after the P&R ruling.

- Bibliography.

- Expert group. The TPR should be signed by the different bodies that have taken part in the evaluation. The MAH, Scientific Societies and Patient Associations that have been contacted during the procedure shall be mentioned as well.

Finally, please note that the above structure of the TPR is included in the SOP for TPRs[8], and that the legal status of such SOP has been indirectly questioned since it represents a direct development of the Plan to Consolidate TPRs, which is currently under legal dispute. Please refer to Q3 (Section II) above for further reference.

5. Which are the questions to focus on when preparing a HTA dossier in your country?

TPRs usually follow the so-called “PICO” Process. PICO is a mnemonic used to describe the four main elements of the process which are: Population/patients (P): health problem and patient population to which it is to be applied; Intervention (I): medicinal product/therapy assessed; Comparators (C); and Outcome (O): relevant clinical variables.

6. Which are the questions to focus on when preparing a HTA dossier in your country?

In our experience, the key elements of the HTA assessment usually revolve around the selection of comparators, the relevant clinical variables and the thresholds of clinical relevance. Such issues should be carefully assessed by companies in order to be able to provide clear studies and documentation to the authorities supporting its view.

[1] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/Comite_Asesor_PFSNS.htm

[2] Accessible at: https://gruposdetrabajo.sefh.es/genesis/genesis/Documents/GUIA_EE_IP_GENESIS-SEFH_19_01_2017.pdf

[3] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[4] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[5] Accessible at: https://gruposdetrabajo.sefh.es/genesis/genesis/Documents/GUIA_EE_IP_GENESIS-SEFH_19_01_2017.pdf

[6] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[7] Accessible at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

[8] See Section 2 of the SOP for TPRs available at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/en/profesionales/farmacia/IPT/home.htm

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

7. Data Requeriments: Spain

1. In addition to the clinical data obtained through clinical studies please list the data required for:

a. Market approval

Generally speaking, for getting a marketing authorization of a medicinal product, the applicant needs to provide sufficient information to demonstrate that the relevant product fulfills the established quality requirements, is safe under normal conditions of use, is effective in the therapeutic indications, is correctly identified, and provides the patient with the necessary information.

b. Pricing Decisions

As discussed above (see Question 1, Section III), reimbursement decisions in Spain are based on the criteria listed in art. 92 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015. On the basis of that, and to specifically answer this question, it can be said that the data required for reimbursement decisions are those that allow the company to prove that its product complies with art. 92 requirements. Spanish law does not provide further criteria as how these data should be, which means that companies are free to prepare such data as they deem convenient.

c. Reimbursement Decisions

As discussed above (see Question 1, Section IV), Spanish law contemplates a “cost plus” system to determine the PVL of medicinal products. Under such “cost plus” system the maximum PVL should respond to the cost of the product plus a given profit margin. This is what Royal Decree 271/1990 contemplates in accordance with the provisions of Directive EC 89/105. Considering this, companies should submit technical accounting and financial documentation necessary to determine the “full cost” of the medicinal product.

As a matter of practice, this is not the criteria actually used by the DGCC/CIPM to set the price of medicinal products (for further details see Question 1 Section III). The documents that really need to be provided and may have a true impact on the P&R Procedure include comparative pharmaco-economic evaluations, list of prices of the product in other EU Member States, or list of activities performed by the company in Spain (R&D, manufacturing, etc.).

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

8. Managed Entry Agreements: Spain

1. Are there any Managed entry agreements in place in your country? (If so, please list them)

Yes, there are managed entry agreements in Spain. The most frequent Managed Entry Agreements (MEAs) are financial and performance-based agreements (both at patient and population level).

2. Describe the fundamentals of the Managed entry Agreement, its rationale and the process for implementing it. When should each Managed Entry Agreement be considered? Which are the specific requirements to implement each Managed Entry Agreement? What are the potential challenges associated with each Managed Entry Agreement?

Financial MEAs

In our experience, the most frequent financial MEAs in Spain are the following[1]:

- confidential discount: an unconditional reduction of the PVL is agreed in a confidential contract, taking the form of an up-front discount or an ex-post rebate refunded by the firm.

- patient-level treatment or expenditure cap: a patient-level treatment (number of products, dosage or duration) or expenditure ceiling is agreed on, and the firm provides products exceeding the cap free of charge.

- population level expenditure cap: an aggregate expenditure ceiling for all patients/ a defined number of patients treated is agreed on, and the firm provides products exceeding the cap free of charge.

- population level price-volume agreement: tiered prices are agreed on, which decrease with increasing aggregate volume purchased for all patients treated.

The main objective of these financial MEAs is to tackle financial uncertainty. This implies that financial MEAs are usually used when the demand of the product is difficult to predict or it is expected to experience a sustained growth over time.

All such agreements may be negotiated and concluded at a national or regional/hospital level. The design of such schemes is easier than performance-based schemes to the extent it is not needed in financial MEAs to define clinical variables or relevant thresholds. The implementation of financial EMAs is also simpler because it does not require the continuous evaluation of patients to categorize them as “respondent” or “not respondent”.

Financial MEAs do not have mandatory specific requirements that they must comply with. A case-by-case negotiation takes place every time a company or the public administration suggests there is a need for this type of arrangement.

With respect to the challenges, one of the most relevant is the incentivization of opportunistic behaviors of the Autonomous Communities and/or hospitals, such as waiting until the cap or the next discount tranche is reached before purchasing products. Financial MEAs can alter consumption trends, which poses a risk to companies and also healthcare systems by increasing the risk of stock-outs caused by peaks in demand. Generally speaking, however, financial MEAs are implemented satisfactorily, and they are regarded as a relevant tool to lower the price of medicinal products and to contribute to the sustainability of the NHS.

Performance-based MEAs

In our experience, the most frequent performance based MEAs in Spain are the following[2]:

- Patient-level payment by results: payment to the firm for treatment provided is contingent on the achievement of pre-specified response to treatment in each patient. Payers may withhold payment partially or entirely for each patient until the result is achieved, receive full or partial refunds for patients who do not achieve the response, or receive free additional products with which to treat subsequent patients.

- Patient-level conditional treatment continuation: coverage of the treatment is continued only for patients who achieve a pre-specified response to treatment; firms provide products free of charge or discounted for patients who do not achieve results.

The main objective of these financial MEAs is to tackle therapeutic uncertainty. This implies that performance based MEAs are usually used when clinical evidence is not entirely satisfactory and, therefore, a scheme were payors only pay when the product actually works makes more sense.

Performance based MEAs may be negotiated and concluded at a national or regional/hospital level. The design of these schemes normally contemplates the creation of a “monitoring committee” made up of the company and representatives of the Autonomous Community and the MOH. This committee has the task of monitoring the agreement and contributing to the resolution of disputes as to whether or not a patient is a “responder” according to the agreed criteria.

A major challenge for this type of arrangement is related to the fact that some hospitals are not yet very accustomed to performance-based schemes, which results in implementation difficulties. The reporting of follow-up data (which ultimately allows to classify patients into responders and non-responders and to determine payer’s payment obligations) is also a challenge.

On the design side, it is often difficult to determine the relevant clinical variables and cut-off values that dictate into which category each patient falls into.

[1] Reference is made to an OECD report on MEAs where the different types of MEAs are classified and defined. Report accessible at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/6e5e4c0f-en

[2] Reference is made to an OECD report on MEAs where the different types of MEAs are classified and defined. Report accessible at: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/6e5e4c0f-en

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

9. Expenditure Control and Cost-Containment Policies: Spain

1. Please describe the main cost containment policies in place in your country and their fundamental principles:

a. Pricing and impact of generic/biosimilar approval

The entry of generics/biosimilars into the market affects the price of original drugs by three main mechanisms: (i) homogeneous groups (“HG”), (ii) reference groups (“RG”), (iii) market pressure.

Products subject to generic competition are affected by HG, RG and market pressure. Products subject to biosimilar competition are only affected by RG and market pressure to the extent HG only includes, as we will see, products that are totally interchangeable (and biological products are not).

As a preliminary comment, it is relevant to note that in Spain generics are usually reimbursed with an approximate 40% discount vs the originator; compared to a 20-30% discount for biosimilars.

Homogeneous Associations

As soon reimbursement is approved for a generic, it will be included in a HG with the reference product. Each HG comprises all products that are identical (same SKU).

The prices of each HG are fixed for the first time on day 1 of any month (“M”) on the basis of the information included in the Nomenclator as of day 20 of month M-1. Once so fixed, they are updated monthly and then quarterly.

During month M, once each HG includes the original and its generic versions, unless the MAH of the original lowers the price of the original product to the level of the generics, it will lose all reimbursed prescriptions where the product is identified by its active principle because the pharmacist, in such case, must dispense the product with the lowest price in the HG.

Reference Groups

Reference groups also affect the price of originators. The effect of the launch of a biosimilar/generic on the originator’s price through reference groups, however, is not immediate. Originator’s price will not have to be reduced until a reference group for the medicinal product is created, and this may take some time after the launch of the biosimilar/generic.

As to when and how a reference price group is created, this will depend on the date on which the biosimilar/generic is launched. Under the current legislation (Royal Decree 177/2014), the MOH approves a reference price list every year on the basis of the information in the database for reimbursed and marketed products as of April 1st. If the biosimilar/generic is launched before 15th March of any year (“N”), then it will appear as reimbursed and marketed on April 1 of such year N, and the reference price group will be created and will apply sometime in Q3 or Q4 of year N. If the generic/biosimilar is launched after 15 March of year N, then it will not appear as reimbursed and marketed on April 1 of such year N, and the reference price group will not be created until Q3 or Q4 of year N+1.

As per the magnitude of the price decrease, we note that, upon biosimilar/generic inclusion in the reference price system, originator’s PVL per DDD (which is the assumed average maintenance dose per day) will be reduced to the level of the “reference price” of the group. Such reference price is fixed on the value presented by the lowest cost of the treatment per day of the presentations of the medicinal products included in the group.

As long as the lowest cost of the treatment per day will most likely be set by the new biosimilar/generic, the practical effect of the application of the reference price system will be the reduction of originators’ PVL per DDD to the level of the PVL per DDD of the biosimilar or generic medicinal product.

Market Pressure

Leaving aside the compulsory price reduction that may apply via HG and/or RG, it is important to mention that the launch of generics or biosimilars usually result in substantial market pressure to reduce prices as of the day of launch.

b. Clawback/Payback/Discounts/Rebates

Royal Decree-Law 8/2010 contemplates the following mandatory deductions on medicinal products:

- Reimbursed retail products are subject to a compulsory 7.5% discount. Pharmacies apply a deduction of 7.5% on the retail price. For the purposes of the application and distribution of this deduction among all agents of the pharmaceutical chain, distributors apply the same deduction (7.5%) on the distributor’s selling price (i.e., price at which the distributor sells the product to the pharmacy), and manufacturers also apply a deduction of 7.5 % on the maximum industrial price (i.e., price at which manufacturer sells the product to the distributor).

- Hospital-use products are also subject to a 7.5% compulsory discount on the “purchase price”.

The above-mentioned deductions do not apply to generic medicinal products or those subject to the reference price system.

The 7.5% discount shall be reduced to 4% in case of orphan drugs; and increased to 15% for products that have no generic/biosimilar competition and that have been reimbursed with public funds for a minimum of ten years (or eleven years in the case a new indication for the very same product was authorized). The mandatory 15% discount does not apply to medicinal products protected by product patents in all EU Member States.

c. Existence of Price/Volume agreements in the frame of public tendering

Price/volume arrangements are not unusual in public tendering. They are used to reduce the average price of the contract and to contribute to the overall sustainability of the system. The terms of each arrangement depend on the particularities of each case and the relevant contracting body.

d. Existence of price freezes and cuts

It is uncommon to freeze or drastically reduce the prices of medicinal products. However, there have been instances where such actions have been taken. This was the case in 2010 and 2012.

In 2010, amid the economic and financial crisis in Spain, Royal Decree-Law 4/2010 was enacted to rationalize pharmaceutical expenditure by the NHS. This Royal Decree-Law introduced a reduction in the price of all generic medicinal products included in the pharmaceutical provision of the NHS.

In 2012, a total of 417 medicinal products were excluded from the pharmaceutical provision, citing reasons such as their indication for the treatment of minor symptoms.

Apart from such exceptional measures, the MOH regularly oversees the pharmaceutical expenditure in those therapeutic areas that pose a significant cost to the NHS. If the expenditure in these areas exceeds the expected levels, the MOH may implement monitoring measures.

e. Post-launch monitoring of prescriptions/sales

Prescriptions may be subject to a “Visa” if healthcare or economic reasons justify such measure. Art. 92.1 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 states that in order to guarantee the rational use of medicines, the MOH may subject medicinal products to special reservations and specific conditions for their prescription, dispensing and use.

Visas may only be imposed under the terms contemplated in c which contemplates that the MOH may only impose a Visa in three scenarios: (i) If the product is classified as a restricted prescription product (i.e., hospital use products, hospital diagnosis products or products requiring a specialist prescription and special monitoring), (ii) if the AEMPS decides that the product must be subject to special reservations for reasons of safety or limitation for certain population groups at risk; or (iii) if only some therapeutic indications are reimbursed or if a reduced contribution is applied depending on the type of patient.

The Supreme Court has validated Visas as a valid tool to control the prescription and use of medicinal products in the scenarios and for the objectives laid down above.

On some occasions, some Autonomous Communities have implemented prescription control programs with effects similar to those of a Visa. This type of measure is only possible with the prior agreement of the CISNS.

f. Existence of Generic Substitution Policies

Generic and biosimilar have different substitution regimes. Biological medicinal products are non-eligible for substitution. In this regard, art. 1 of MOH Order SCO/2874/2007 states that biological products “shall not be substituted when dispensed without the express authorization of the prescribing doctor”. Because of this, biological products are not included by the MOH in the so called “Homogeneous Groups”, which are lists of products that may be substituted.

Generics are, indeed, eligible for substitution at a pharmacy level.

g. At prescriber level

It is not unusual for Autonomous Communities and hospitals to put in place systems aiming to promote the prescription of generic and biosimilar medicinal products. Some of such systems were declared illegal by the Courts because they affected in an unacceptable way the freedom of prescription of physicians.

As a matter of practice, it is known that some regional authorities or hospitals stimulate the use of biosimilars and generics through mechanisms that are not totally transparent, and which may include the following: informal recommendations and informative actions, include biosimilars and generics as first option in Clinical Guides, request to prescribers to select patients eligible for switching, setting up minimum quotas for biosimilars for naive patients, setting up minimum quotas for biosimilars and generics on a global basis, considering the level of consumption of generics and biosimilars as a KPI when measuring efficiency of a hospital or fixing a maximum budget per hospital in connection with a given therapy.

h. At retail level

Reimbursed medicinal products that patients obtain at retail pharmacies are subject to co-payment rules, under which the patient must pay part of the price of the medicinal product. The co-payment percentage depends on the type of product and the type of patient.

2. Are there any other policies in place aiming at cost control via incentive programs targeting the different actors (pharma companies, wholesalers, retailers, prescribers etc.)?

In late 2015, Farmaindustria (the association of the innovative Spanish pharmaceutical industry) reached an agreement with the Spanish Government (the “Farmaindustria Agreement”) under which pharmaceutical expenditure was not to grow more than real GDP growth.

The agreement contemplated chargebacks to be paid by pharmaceutical companies in the event that the expenditure exceeded the agreed ratio. The agreement also contemplated that in the situation that the expenditure exceeded said ratio, special measures to rationalize the use of medicinal products may be adopted. These measures, in essence, would imply barriers for prescription of high-budgetary-impact drugs.

The Farmaindustria Agreement was fully effective until 30 June 2020. Since then, Farmaindustria and the Spanish Government have been negotiating a new agreement. No agreement has been reached so far. In 2022, the agreement was included in the agenda for the Stability Plan from 2022 to 2025 presented by the Spanish Government to the European Commission.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

10. Essential Drug List: Spain

1. Has an essential or priority drug list been published in your country? (If so provide the link)

Yes. Three types of lists have been published by the AEMPS:

- “Essential medicinal products”: according to the WHO definition, these are the necessary medicinal products for a basic health system.

- “Critical medicinal products”: a subgroup of essential medicinal products for which there should never be supply problems in the health system.

- “Strategic medicinal products”: a subgroup of critical medicinal products for which additional measures, whether regulatory, economic or otherwise, are considered necessary to ensure their maintenance in the market both because of their need for basic health care and because of the vulnerability of their supply chain.

Such lists are published at the AEMPS’s official website.[1]

2. If so what is the impact/consequences of a drug being published on the EDL/PDL:

a. In terms of market approval

Three main consequences are worth mentioning in this area.

First, AEMPS has put in place the necessary mechanisms to speed up the administrative procedures and the evaluation of changes to the MA of these medicinal products. To this end, it has established shorter deadlines for the validation of applications and a prioritized evaluation of the variations requested.

Second, AEMPS offers scientific and regulatory advice to laboratories. This advice can be provided throughout the application process or facilitating the submission of the registration dossier. The evaluation of authorization applications for medicinal products submitted through the national route will be expedited as a matter of preference in order to favor the availability of these medicinal products on the market in the shortest possible time.

Third, the AEMPS will prioritize the granting of Spanish slots as a reference member state (RMS) for authorization applications through European procedures in order to favor the internationalization of these strategic medicinal products.

b. In terms of reimbursement

The inclusion of a product in such lists does not have a direct impact on reimbursement decisions. Being included in such lists, however, may facilitate product’s compliance with art. 92 of Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 and, therefore, may indirectly facilitate reimbursement. Please refer to Question 1, Section III above.

c. In terms of pricing

Essential products may have preferential treatment in the context of reference pricing. As discussed, the inclusion of a medicinal product into a reference group implies the reduction of the PVL of the originator per DDD to the level of the PVL per DDD of the biosimilar/generic. Such reduction may be effective immediately (general rule) or gradually during several years in accordance with specific rules contemplated in art. 4 of Royal Decree 177/2014 (“Weighted Average”). Under the Weighted Average regime, the price of the original product is gradually lowered year by year in a staircase fashion.

The preferential treatment of essential medicinal products consists of freezing their price if they are subject to the “Weighted average” regime. For such special regime to apply, companies must demonstrate that the price freeze is necessary to ensure the availability of the medicinal product and that the essential medicinal product has no reimbursed alternatives.

d. In terms of value assessment and pharmacoeconomic requirements

As far as we are aware, being in the abovementioned lists does not have any direct impact on value assessments or pharmacoeconomic requirements. Indirectly, it may have some impact to the extent that being in such lists necessarily means that the product is considered critical and indispensable for the proper functioning of the system, which implicitly implies a recognition of value.

3. Do value assessment and pharmacoeconomic data play a role in terms of access to the list?

No. Inclusion in the mentioned lists is based on criticality and vulnerability criteria, not economic assessments.

[1] Accessible at: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/medicamentos-estrategicos/

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

11. Orphan Drugs: Spain

1. What is the definition of an orphan drug in your country?

In Spain there is no particularity in relation to the definition of “orphan drug” derived from the Regulation (EC) No 141/2000.

Under Regulation (EC) No 141/2000 a medicinal product shall be designated as an orphan medicinal product if its sponsor can establish: (i) that it is intended for the diagnosis, prevention or treatment of a life-threatening or chronically debilitating condition affecting not more than five in 10 thousand persons in the Community when the application is made, or that it is intended for the diagnosis, prevention or treatment of a life-threatening, seriously debilitating or serious and chronic condition in the Community and that without incentives it is unlikely that the marketing of the medicinal product in the Community would generate sufficient return to justify the necessary investment; and (ii) that there exists no satisfactory method of diagnosis, prevention or treatment of the condition in question that has been authorised in the Community or, if such method exists, that the medicinal product will be of significant benefit to those affected by that condition.

2. Describe the pricing process of orphan drugs in your country.

There are no particularities for orphan drugs when it comes to pricing. The same P&R Procedure for non-orphan drugs apply. Please refer to Question 1, Section III above.

Further, it is relevant to note that certain orphan drugs are exempt for being included in the reference price system, which means that they have a preferential treatment in this respect. Four elements are relevant for such purposes.

First. On 3 March 2020, a Resolution of the Council of Ministers excluded orphan medicinal products from the reference price system under the following conditions: that no “therapeutic alternative” exists or, otherwise, that the relevant orphan medicinal product provides a “significant clinical benefit”.

Second. On 2 December 2021, the Spanish National High Court issued an important judgment stating, in essence, that orphan products shall be unconditionally excluded from the reference price system. According to such judgement, subjecting orphan drugs to the reference price system goes against the spirit/objectives of Regulation 141/2000 on orphan drugs. This Judgment was not appealed and, therefore, became final.

Third. In February 2022, the Spanish Supreme Court issued two judgements that concluded that it is incorrect to argue that the principle of primacy of EU law and Regulation 141/2000 enable the unconditional non-application of the reference price system to orphan drugs. According to the Supreme Court, orphan drugs are, indeed, subject to the reference price system by virtue of article 98(2) of RDL 1/2015, which does not contravene Regulation 141/2000. As per the Supreme Court, if orphan drugs are to be excluded from the reference price system, this should be done under the terms of the Resolution of the Council of Ministers of 3 March 2020 mentioned above.

Fourth. The RPO updating the reference price system for 2022 originally included some orphan medicinal products but this was identified as an error, and they were later on excluded. The RPO draft updating the reference price system for 2023 does not include orphan drugs.

3. Describe the reimbursement process of orphan drugs in your country.

There are no particularities for orphan drugs when it comes to reimbursement decisions. The same P&R Procedure for non-orphan drugs apply. Please refer to Question 1, Section III above.

4. Other than the clinical studies required, do the data and studies required for the pricing and reimbursement of orphan drugs differ from that of other drugs?

No.

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

12. Vaccines: Spain

1. What is the definition of a vaccine in your country?

The AEMPS defines a vaccine as an antigen-containing preparation capable of inducing specific and active immunity in humans against an infecting agent or the toxin or antigen elaborated by it. Immune responses include the induction of innate and adaptive (cellular and humoral) mechanisms of the immune system.[1]

2. What are the classifications of vaccines in your country?

The AEMPS distinguishes three types of vaccines[2]:

- Uncombined vaccines: vaccines containing antigens from a single pathogen or a single strain of the infectious agent. Uncombined vaccines can be “non-combination bacterial”, or “non-combination viral”.

- Combined vaccines: vaccines containing, in the same product, antigens from different pathogens or different serogroups, serotypes or strains of the same infectious agent that are administered simultaneously. Combined vaccines can be classified as: “bacterial”, “viral” or “bacterial-viral”.

- Conjugated vaccines, or “flat vaccines”: inactivated bacterial vaccines that contain only a fraction of the microorganism, the polysaccharides, bound to a carrier protein that helps to enhance and increase the immune response, switching from thymus-independent (humoral) to thymus-dependent (cells, leading to immunological memory) immunity.

3. Describe the pricing process for vaccines in your country (based on their classifications).

There are no particularities for vaccines when it comes to pricing. The same P&R Procedure for non-vaccine products apply. Please refer to Question 1, Section III above.

4. Describe the reimbursement approval process for vaccines in your country (based on their classifications).

There are no particularities for vaccines when it comes to pricing. The same P&R Procedure for non-vaccine products apply. Please refer to Question 1, Section III above.

5. Other than the clinical studies required, do the data and studies required for the pricing and reimbursement of vaccines differ from that of other drugs?

No.

[1] Accessible at: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/medicamentos-biologicos/vacunas/

[2] Accessible at: https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentos-de-uso-humano/medicamentos-biologicos/vacunas/

Also from this Market Access & Health Technology Assessment

13. Public Procurement and Tendering: Spain

1. Which are the main actors involved in public procurement and tendering?

There is a high degree of decentralisation in public procurement in Spain. Regarding the public procurement and tendering services of medicinal products there are actors involved at a national level (MOH), regional level (the governments of the Autonomous Communities) and local level (hospitals).

2. What are the main characteristics of the public procurement and tendering system?

The European Union regulatory framework has clearly moulded the regulation of public procurement in Spain. Particularly, the national general regulatory framework is set out by Law 9/2017, of 8 November, on Public Sector Contracts (“Law 9/2017”), in force since March 2018, which transposes Directives 2014/23/EU and 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council into national law.

In line with the EU regulatory public procurement framework, Law 9/2017 aims to implement a public procurement system based on the principles of non-discrimination and equal treatment among potential candidates, public notice, free and effective competition, transparency, and efficient public expenditure.

Regarding the contract award procedure, Law 9/2017 establishes five main award procedures: (i) open procedure, (ii) restricted procedure, (iii) negotiated procedure without notice, (iv) competitive dialogue, and (v) association procedure for innovation. Ordinary open or restricted procedures are the general rule. Other proceedings should be reserved for exceptional circumstances.